After World War II, Vannevar Bush, the head of the United States Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), had a lot on his mind.

Bush and OSRD pioneered all of the key research and development for the US during the war — everything from radar to the Manhattan Project.

It's fair to say that OSRD only existed because of Vannevar Bush. Story goes that after Germany invaded France in 1940, Bush (no relation, most likely) presented President Franklin Roosevelt with a single piece of paper outlining a plan to coordinate all wartime military research from American scientists. Roosevelt approved the plan 15 minutes later.

Once the war was finally over, Bush turned his mind to the science of information.

There is increased evidence that we are being bogged down today as specialization extends. The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers—conclusions which he cannot find time to grasp, much less to remember, as they appear.

Even 50 years before the internet, Vannevar was experiencing information overload. It was already impossible to keep track of all the new scientific developments being invented. The rate of overall scientific evolution had vastly outpaced the comprehension of an unaided individual.

There was a new problem: there was too much information.

As all good scientists do, though, Bush invented a solution.

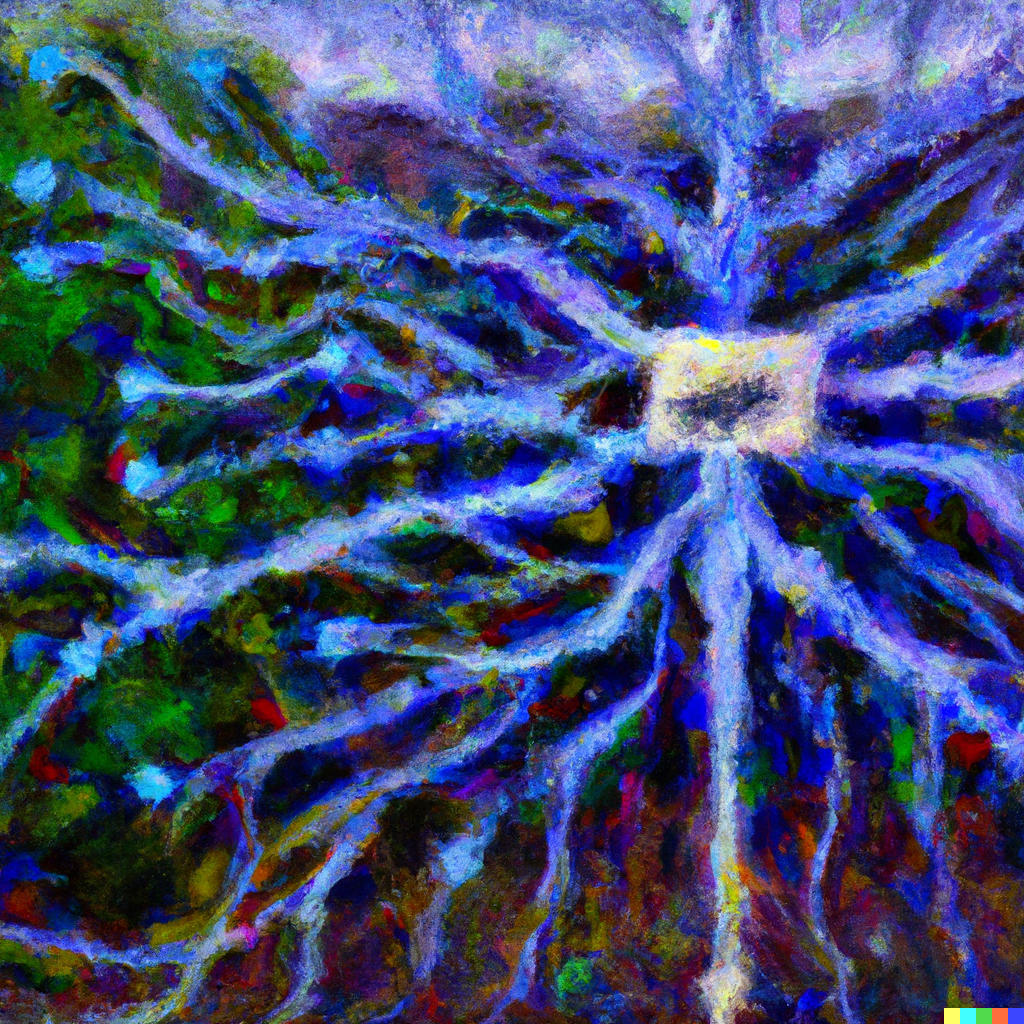

The memex

Before you ask — no, it has nothing to do with memes.

The memex was Vannevar's early interpretation of a computer. Memex stands for “memory expander”. It was a hollowed-out desk with a computer inside that would augment the memory of its user by reminding them of helpful notes and by searching a library of external information.

Bush had been thinking about this idea for years, but it was in July 1945 when he fully described the philosophy of this invention in the seminal essay As We May Think.

The process he describes in the essay is surprisingly similar to that of the modern day knowledge-worker.

There were all these different ways to collect information — a keyboard, microphones, even a head-mounted camera (which I can live without, thanks). The memex would have a file hierarchy and the ability to easily search previous documents.

Creative thought and essentially repetitive thought are very different things. For the latter there are, and may be, powerful mechanical aids. — Vannevar Bush, As We May Think

There was also a system for extrapolating relationships between concepts through links, which would eventually become the inspiration for hypertext — the fundamental idea that the entire modern internet is built upon.

Bush knew that a lot of this stuff was beyond what was possible during his time.

Had a Pharaoh been given detailed and explicit designs of an automobile, and had he understood them completely, it would have taxed the resources of his kingdom to have fashioned the thousands of parts for a single car, and that car would have broken down on the first trip to Giza.

The full As We May Think essay is not brief; it clocks in at 8,114 words, about 35 minutes for the average reader.

But if you want to use technology to make you smarter, As We May Think is required reading.

Today, everyone with a smartphone in their pocket — or access to any computer, laptop, tablet, etc. — has access to their own personal memex.

Building a memex

There are tons of different apps for building your memex.

First, I want to make an important caveat: it’s possible to do this for free, but if you really want to do it the right way, be prepared to spend some money — generally $10 - $20 per month.

Second, let’s make one thing clear: you only get out what you put in. If you do one entry a day you’ll have far less to work with than three entries a day. At the same time, you have to balance your mental stamina to prevent burnout and keep you consistently recording new information.

Finding the app that helps you strike this balance is vital. Strive for the system with the least friction.

- Notion, which I use to organize Platforms and Personalities. Notion’s templates are incredibly robust, covering spreadsheets and databases to calendars to writing. There are shared document features and lots of formatting options. You’ll need to pay for the Personal Pro tier but it’s only $5 per month.

- Roam Research, which has an amazing relational database very much in line with what I think Vannevar Bush was thinking about. They have a community so passionate about their product they jokingly refer to it as the “Roam Cult.” Major downside of Roam is that despite using text, the app feels very proprietary and database exports are complicated. More costly at $15 per month.

- Obsidian, which is very similar to Roam but instead hosts the database on your local machine using plaintext Markdown. Prettier version of Roam with better storage and export options. Free for personal use!

- Evernote, the original note-taking app. I will forever remember Thomas Houston’s incredible 2012 Verge at Work article (and the accompanying video) — this is how I learned about Vannevar Bush in the first place, the original inspiration for building my own memex. $10 per month but tbh... I don’t recommend this to anyone in 2022.

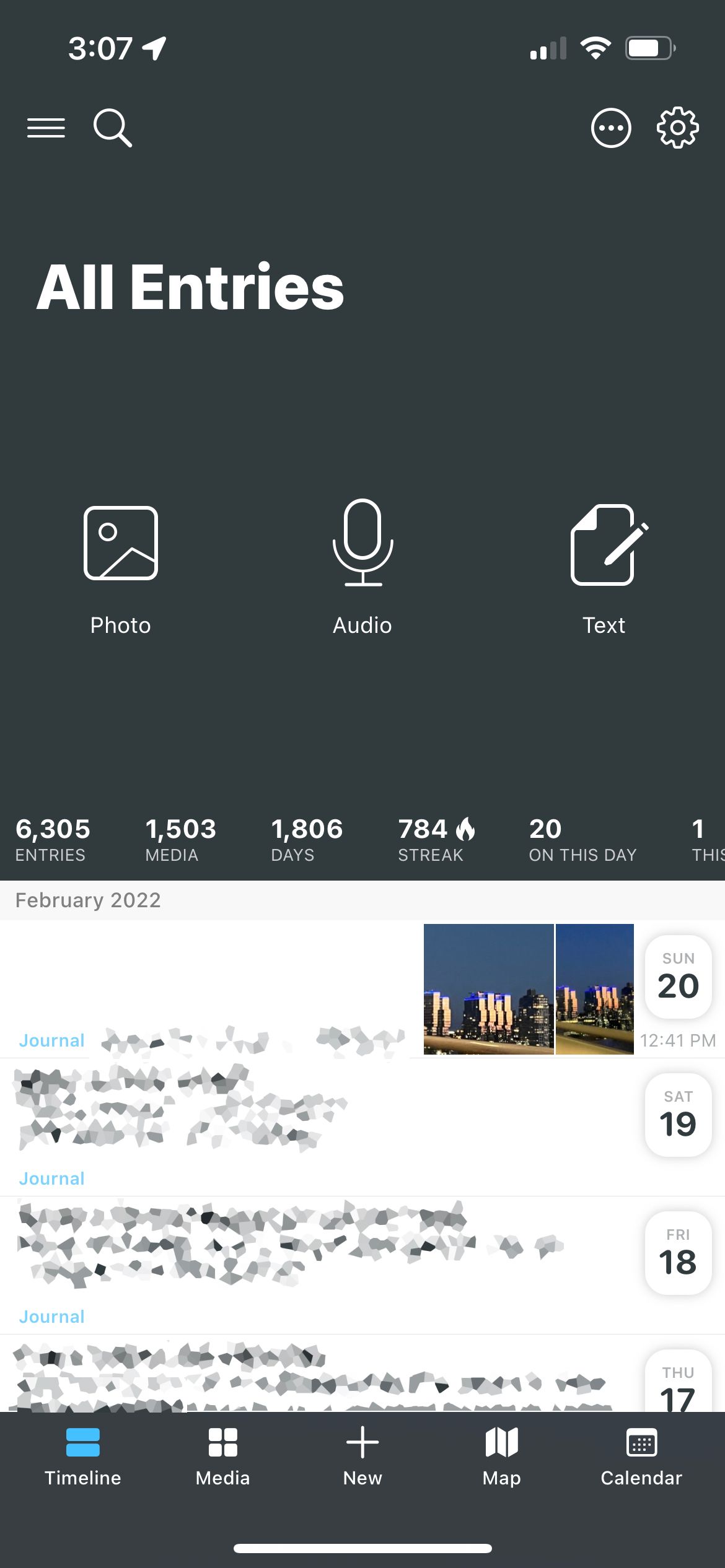

- Day One, my favorite app. It’s like your own personal social network. I’ve been using Day One for nearly a decade and use it as a personal journal and library of ideas. More on how I use it below. Premium version will transcribe your voice memos into text so you can search (it’s awesome). $35 billed annually, so that’s $2.92 per month.

- Omnifocus, the most robust to-do / productivity app out there. If you’re a fan of Getting Things Done, you’ll love this app. Very complicated tagging and folder options. I used to use this but it was too elaborate for me. Only available on iOS. $9.99 per month.

- Things, a to-do app that’s also one of the most beautiful apps out there in any category. I use Things to remind me of things I want to get done in every aspect of my life. Incredibly simple but still has all the features I need. Only available on iOS. A more expensive but one-time purchase in the App Store: $9.99 iPhone app, $19.99 iPad app, $49.99 Mac app.

There are also quite a few modern day personalities who are creating the future of personal memex. These people are all great inspirations if you want to learn about the potential of what a memex can do for you.

David Allen has been a productivity icon for years since he wrote the seminal book Getting Things Done.

Tiago Forte, the founder and author of Building a Second Brain. Tiago was one of the early guys to sell an online course; in it, he teaches how to use Evernote and other apps to “build a second brain” and enhance his memory. His system seems really similar to the one that Thomas Houston described in his Verge at Work column..

Conor White-Sullivan, the founder of Roam Research. He feels like more of a shoot-from-the-hip intellectual compared to Tiago, but very precise with his words. He’s super active on Twitter.

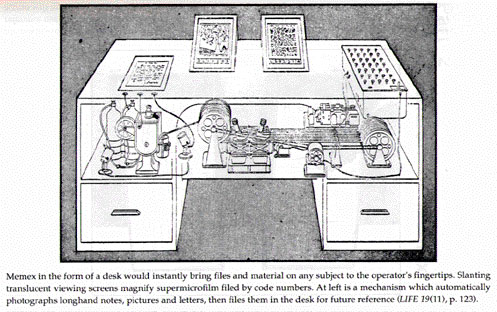

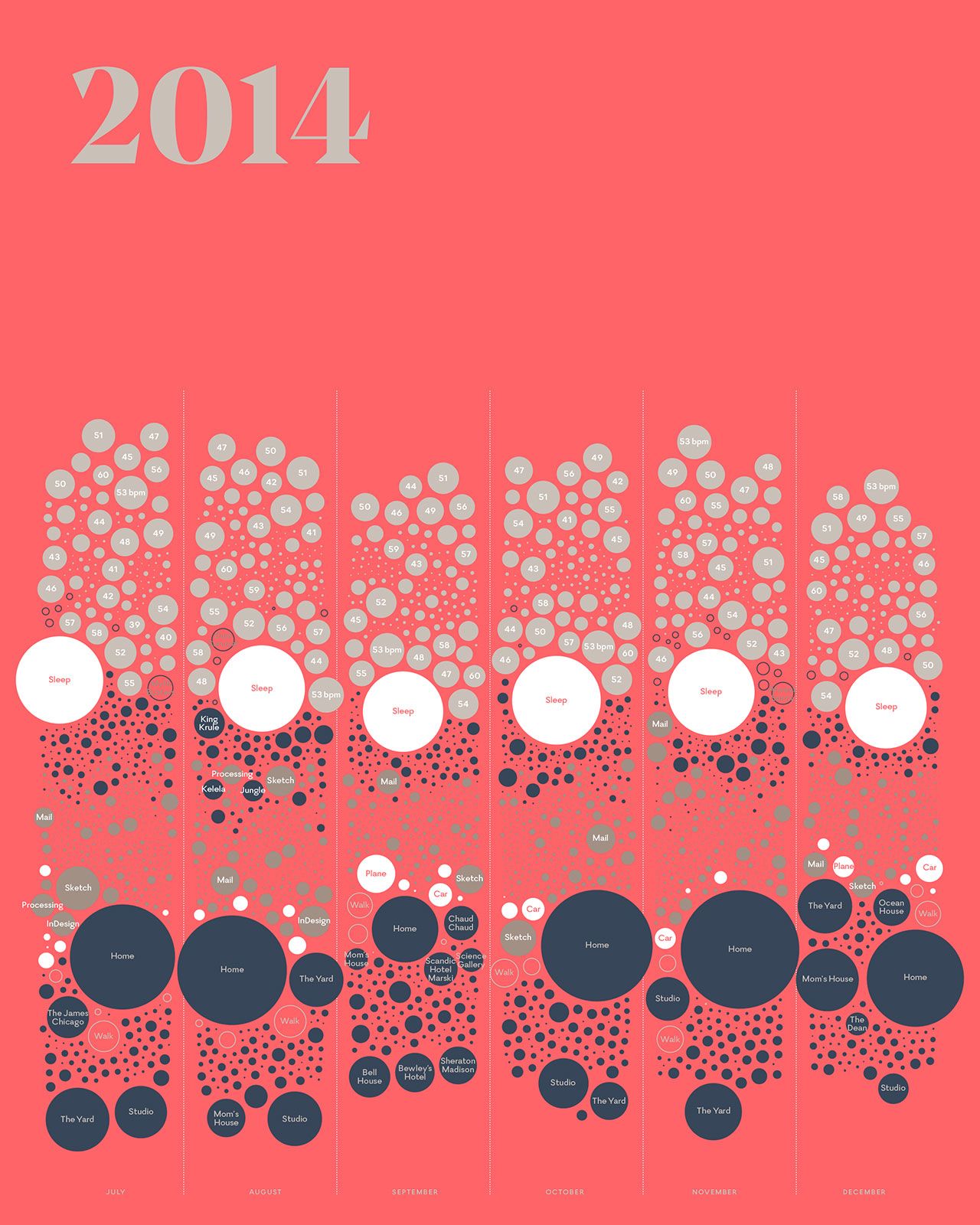

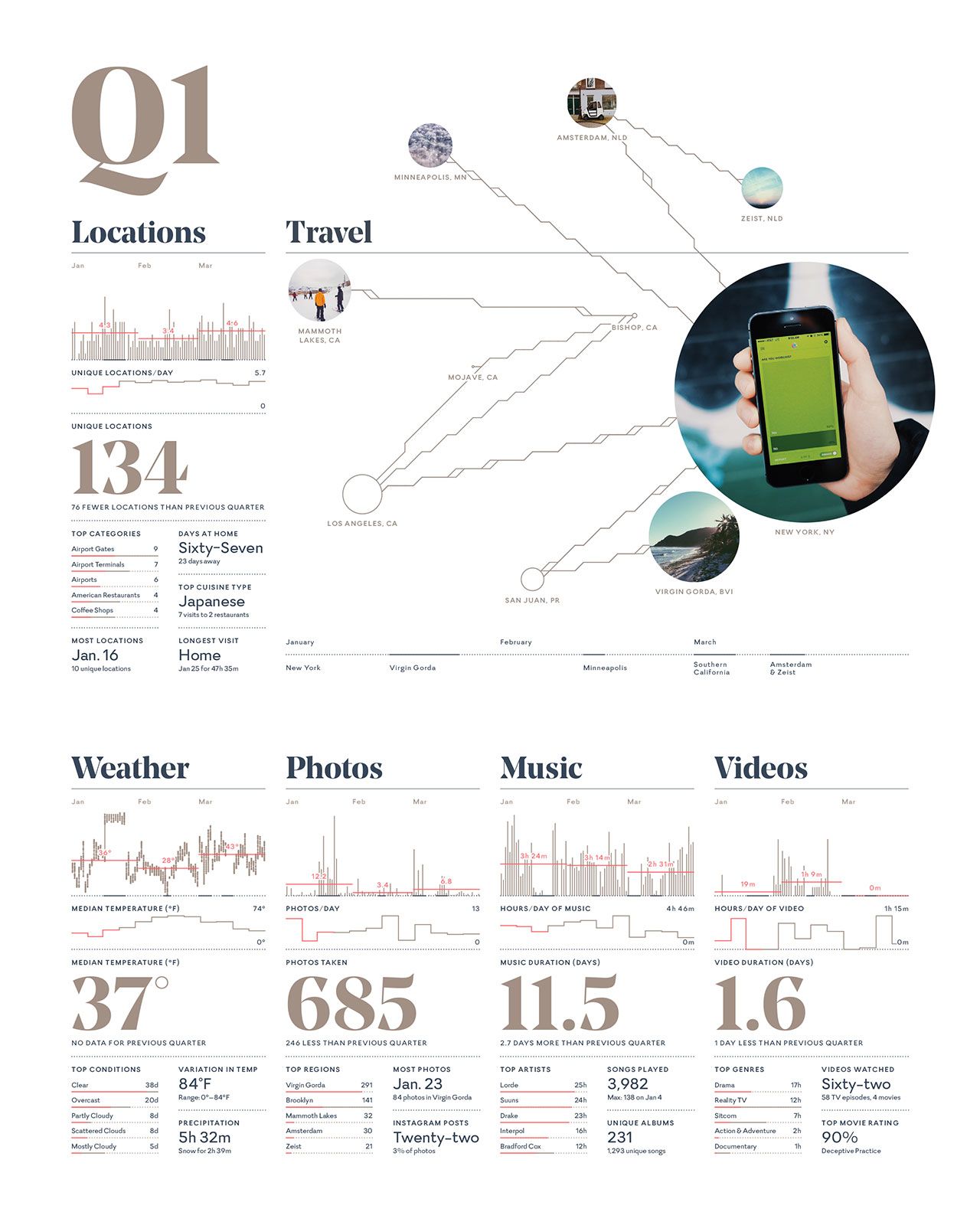

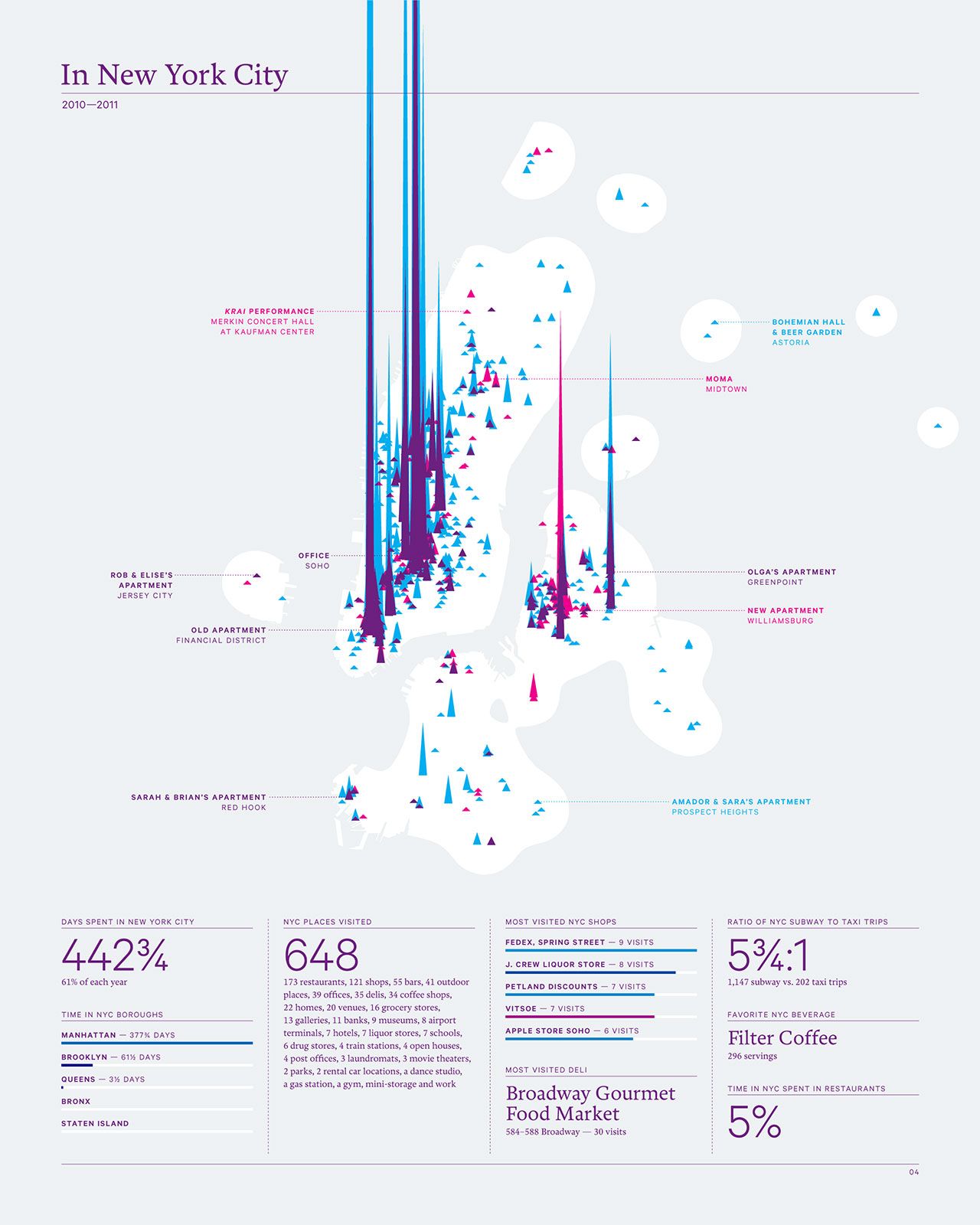

Years ago, Nicholas Felton developed a legendary reputation amongst data visualization nerds for his annual reviews. Felton was incredible intricate with his reporting and analysis. The results are dense, informative, and slightly overwhelming.

Visualizations from NIcholas Felton’s annual reviews in 2014 and 2011.

This is inspirational for me in theory, but far too elaborate to implement in practice. Over time, I’ve learned that I prefer simplicity.

My memex

I’ve been tweaking and testing this system for years. I’ve tried almost all of the high profile apps in this category — everything from Evernote to Notion to Roam to Obsidian. I spent months using Notion, and then Roam. I wrote tons of things when using those apps but had a hard time resurfacing it when I needed it the most. But there are only two apps I really found myself unable to live without.

- Day One

- Things

These apps work perfectly together.

Day One is about information: pictures, videos, voice memos, stories, thoughts, links and ideas. This is my library.

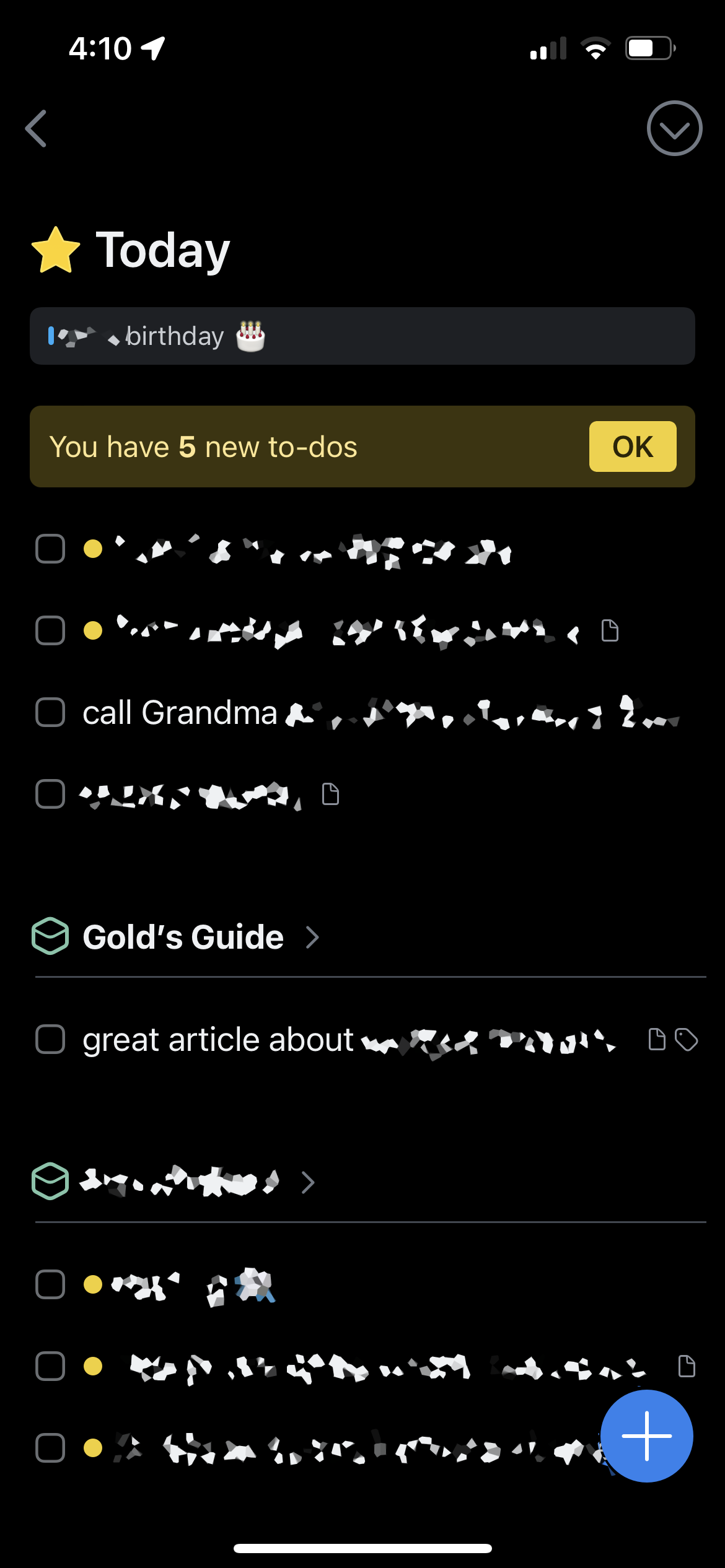

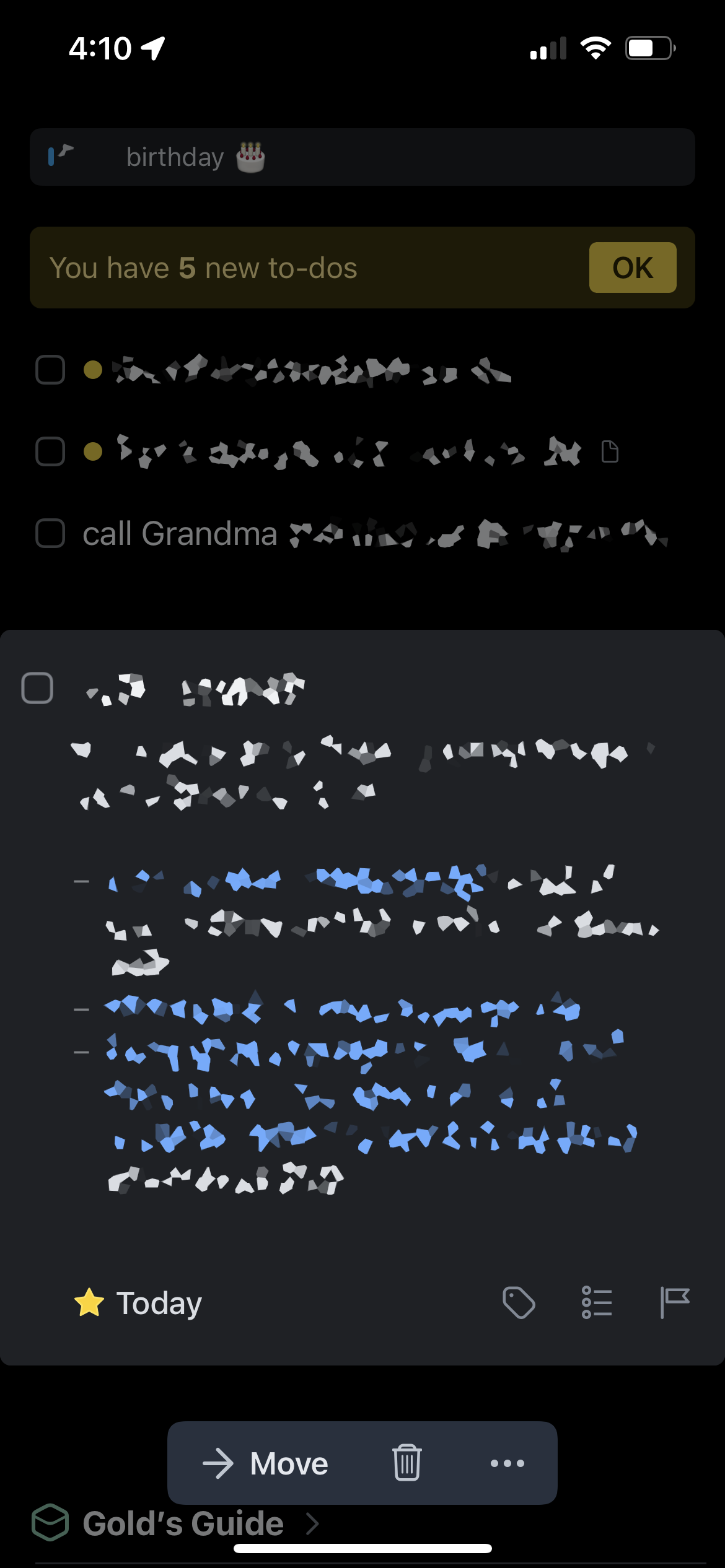

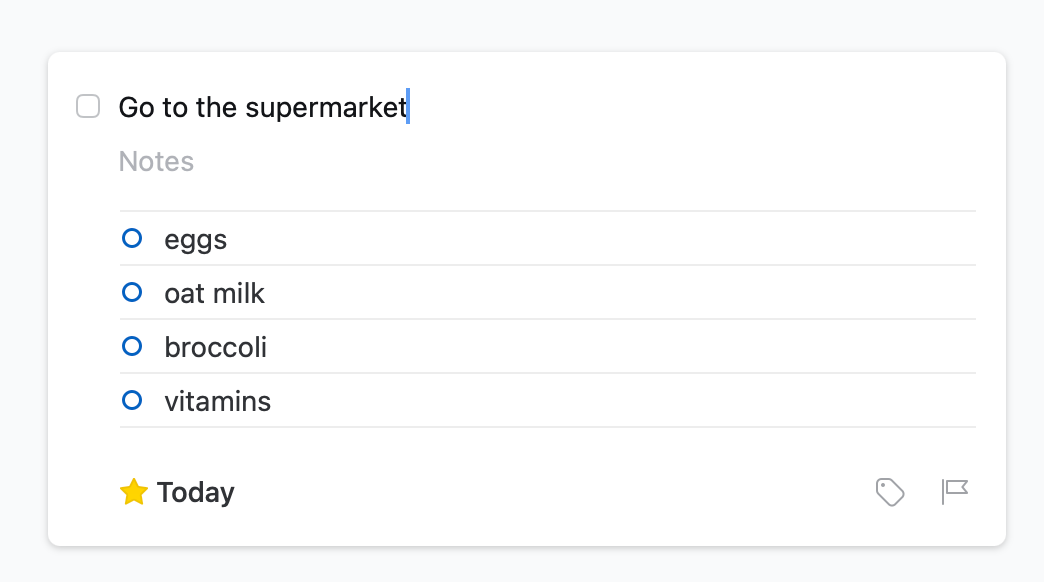

Things is about time: reminders, to-do’s, shopping lists, plans.

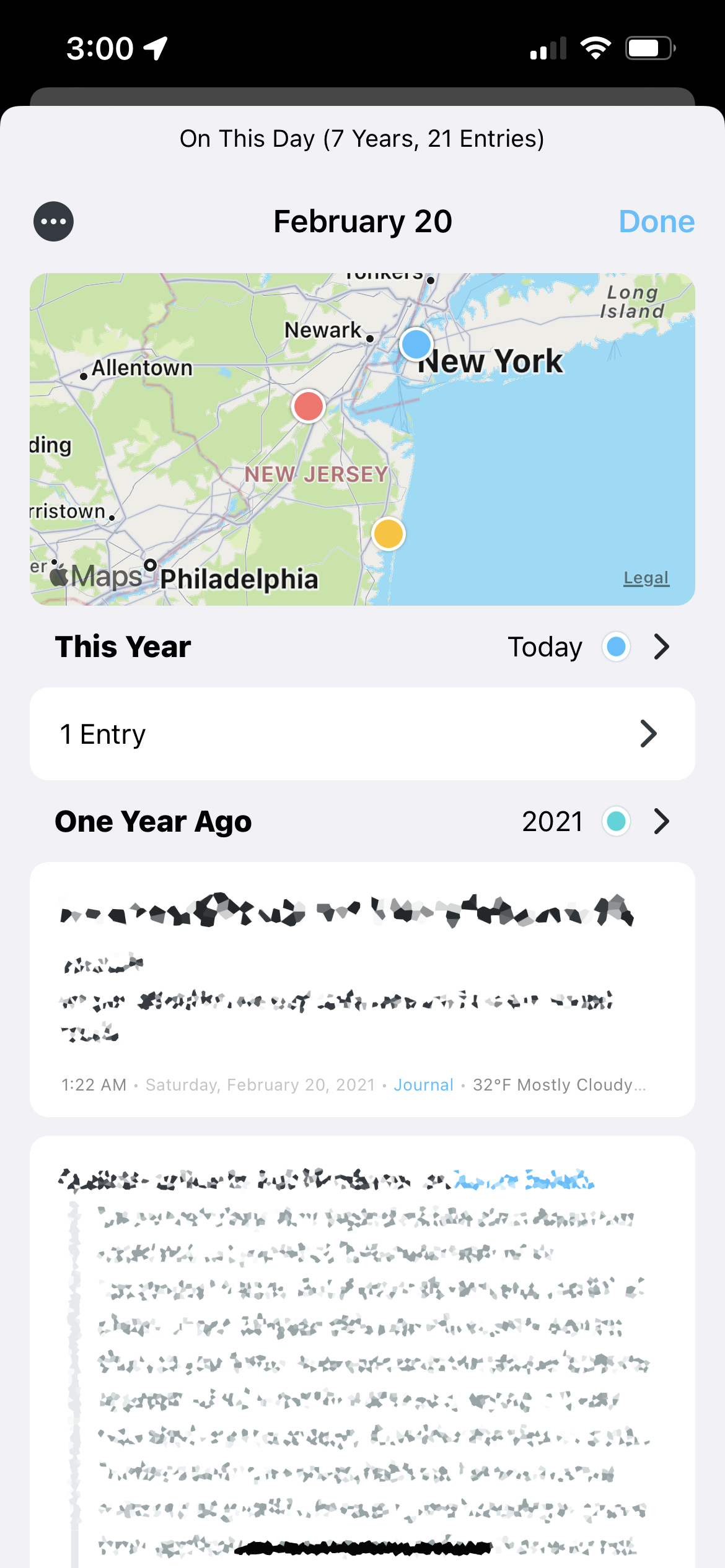

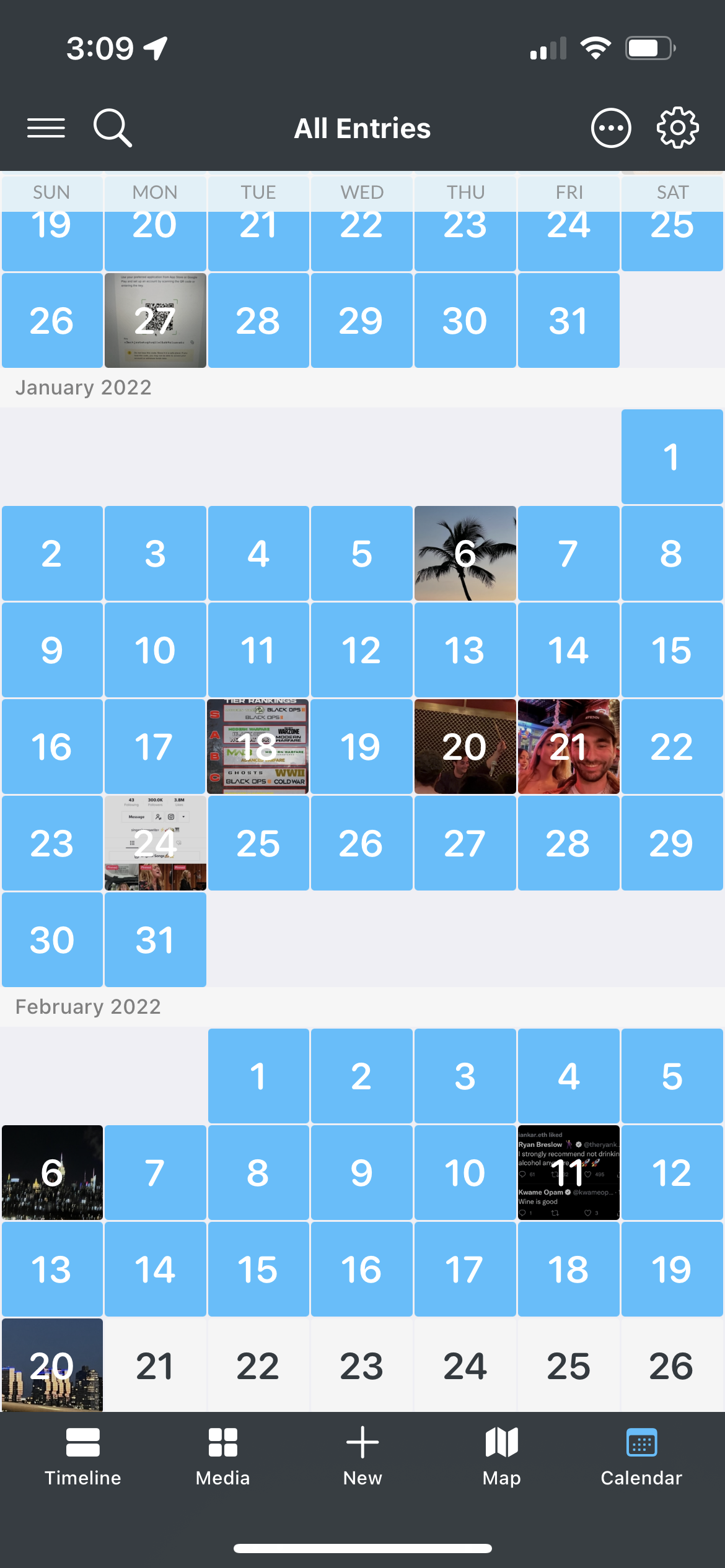

The strengths of one picks up where the weaknesses of the other begins. Day One has an incredible “on this day” feature, a better version of Timehop. I have at least 10 historical entries in my Day One for every day of the calendar year.

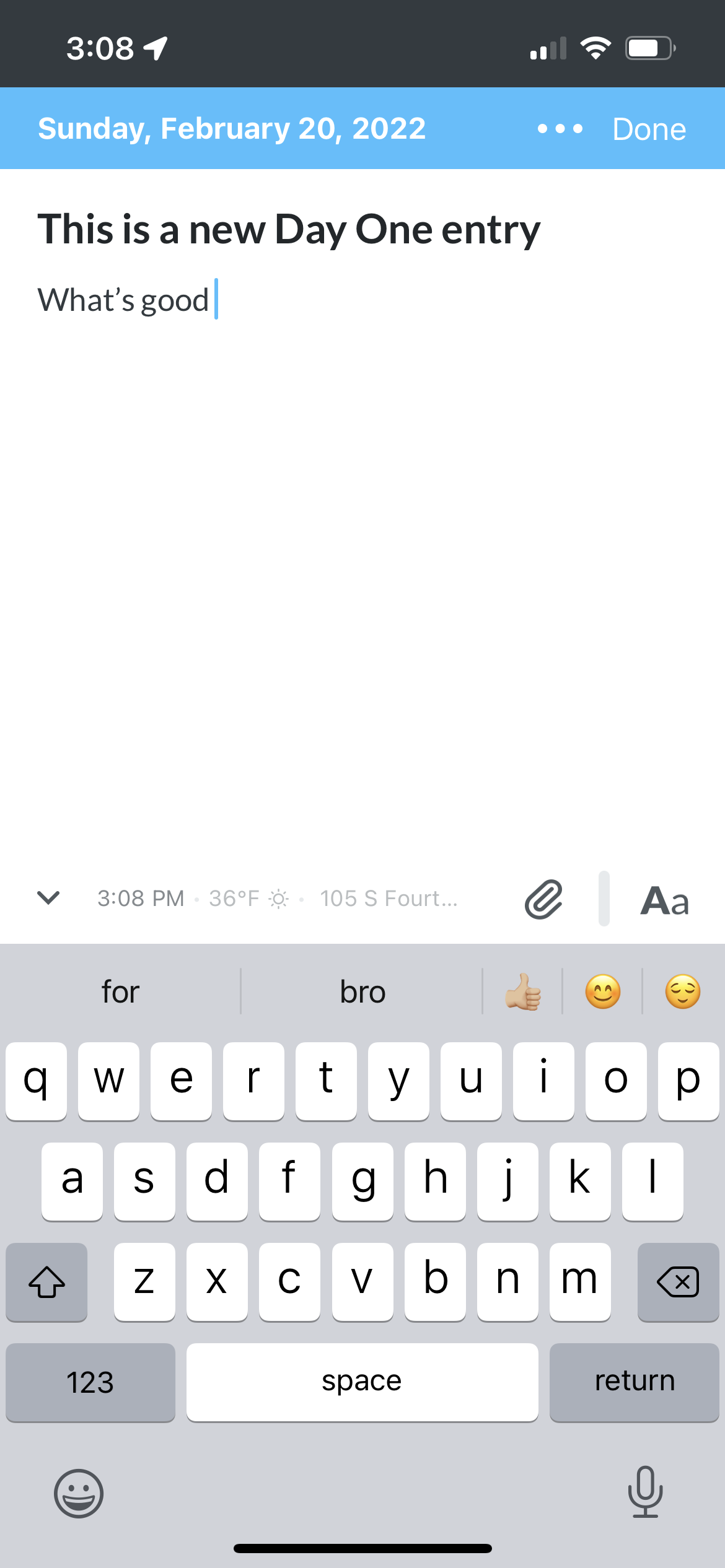

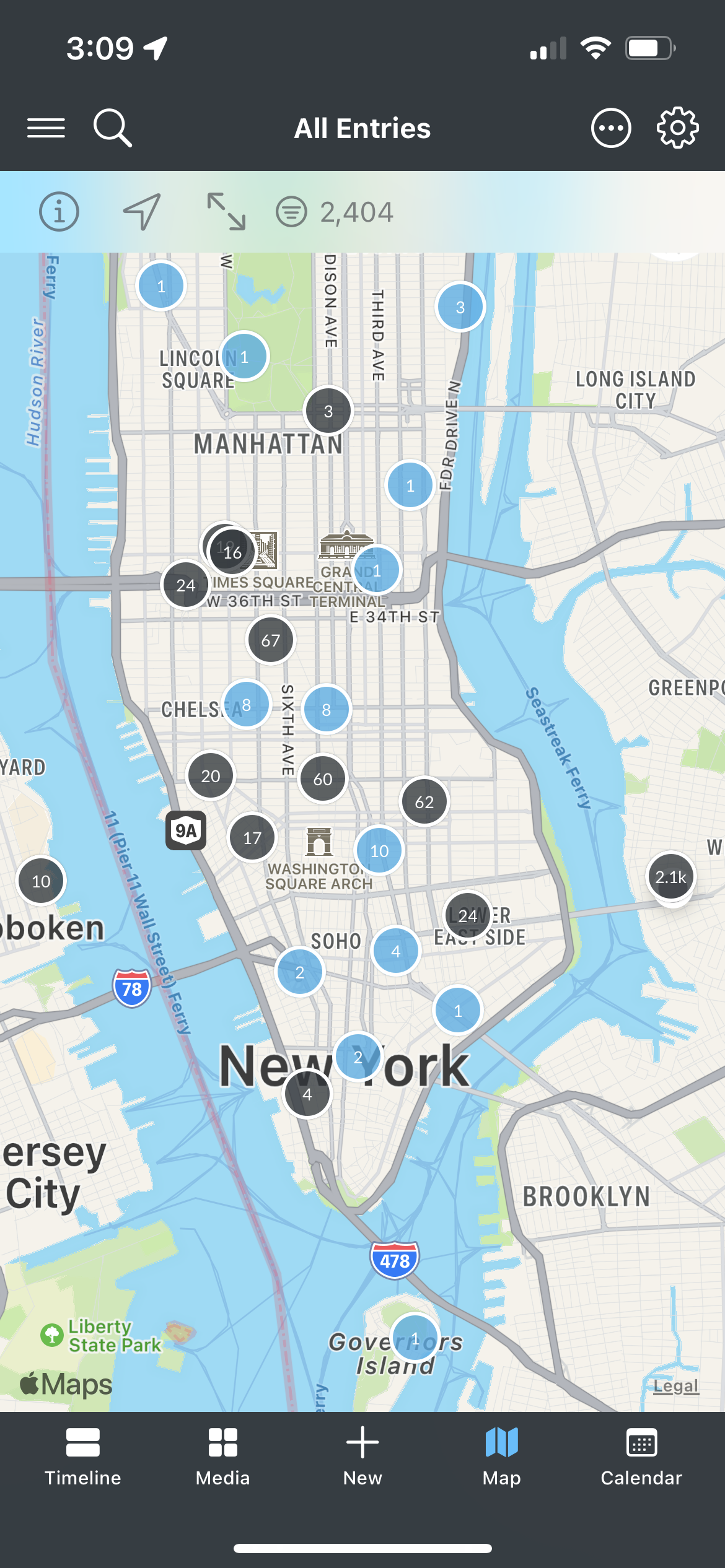

Some screenshots of Day One. If you zoom in the map section you see more precise locations than what is shown here.

If I want to make sure I remember it, it goes into Day One. Then I can search for ideas, people, memories, even locations.

The on this day feature is probably my favorite thing about the app, since it automatically surfaces journal entries I wouldn’t have otherwise found that day. It feels like a horoscope that I wrote myself, for myself — surprisingly often I’ve found that themes will repeat on the same day in different years.

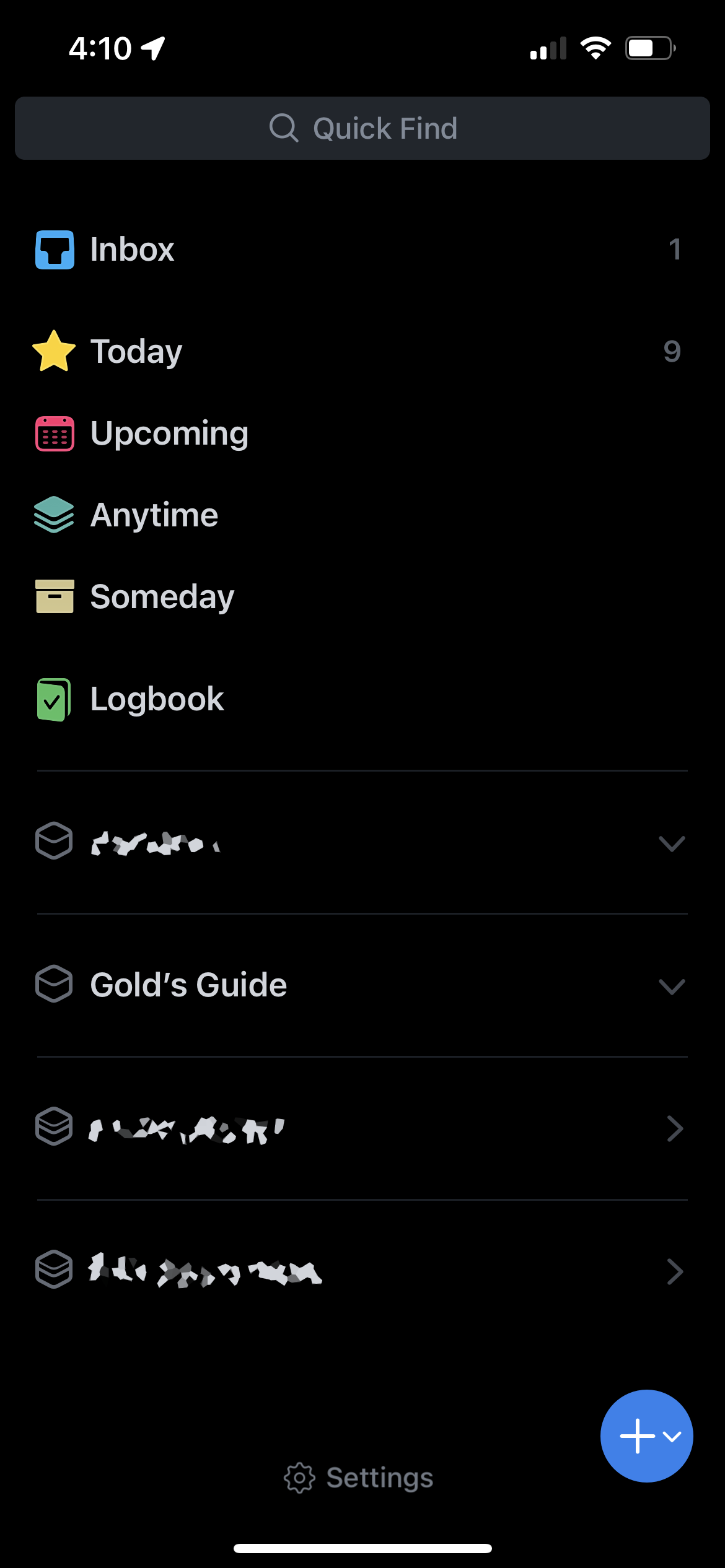

The way I use Things is more practical. This is my space for things that are connected to time. I’ve been known for having a penchant for procrastination that I prevent with Things.

Blurred for privacy.

Whenever I have to do something for work that’ll take more than a few minutes, I create a new item in Things. I give it a title and keep notes inside. There's options for sub-items which are great ways to stack up small victories while working on a project.

You can also create Projects that are made up of multiple items like the above. Things has just the right amount of complexity for me without getting overwhelming.

Day One and Things are apps I use that make me better. Yes, I pay for both of them, but the price is totally worth it — for about $100 I get two apps that significantly enhance my memory.