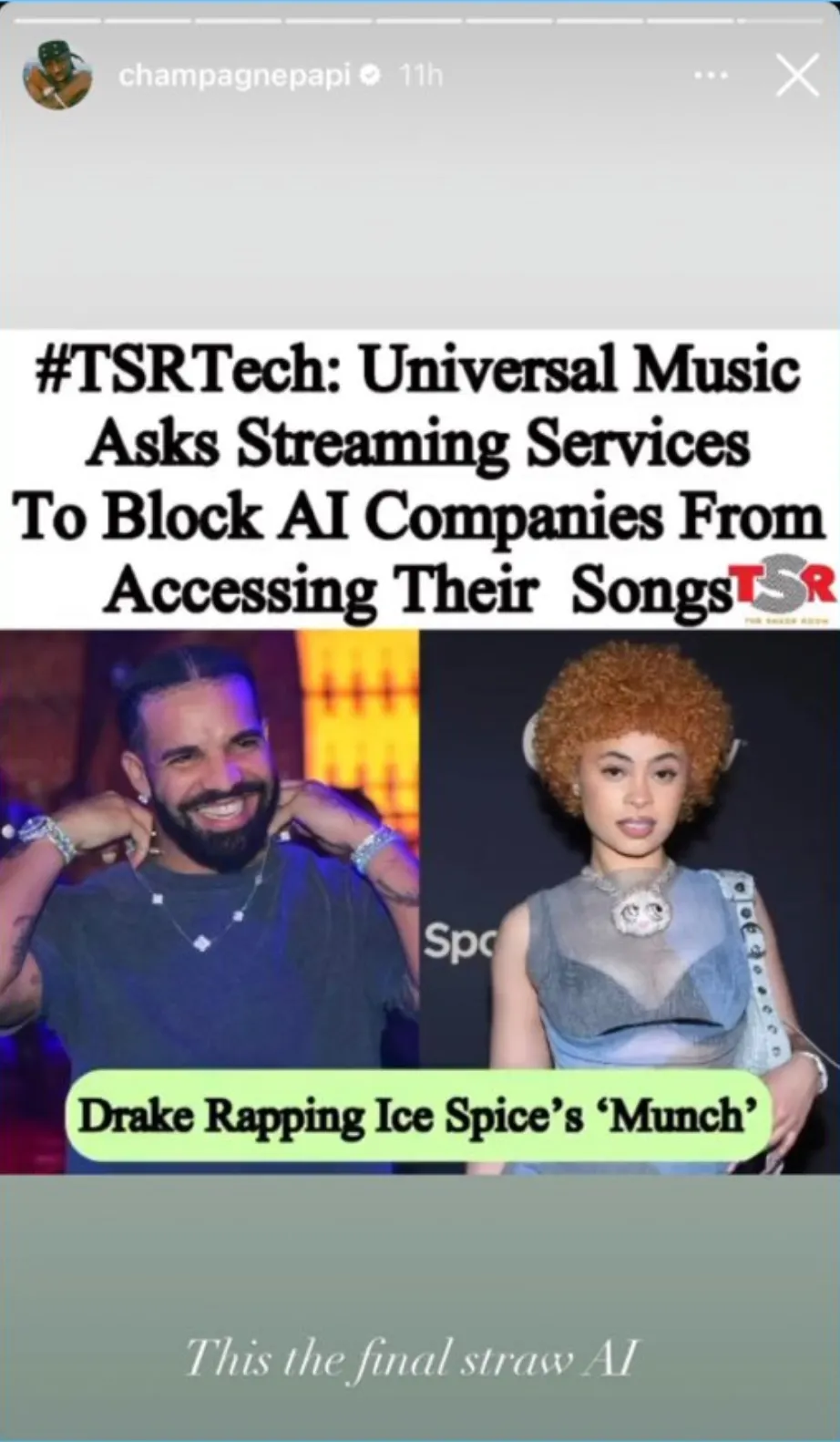

Drake understands how to use memes to market music better than anyone else — so I was somewhat surprised when he apparently gave his record label UMG the green-light to scrub AI generated Drake songs from the internet.

“This the final straw AI”, wrote the world-famous musician in a now-deleted Instagram story. Why? Someone used AI to create a version of the Ice Spice song “Munch” that sounded like Drake was singing it.

Look, I get it — it’s not a good look for Drake to be singing a song with lyrics like that — but Drake is the king of the meme. I kinda expected him to run with it.

Nearly every one of Drake’s album covers has become a meme template; “yolo” and “started from the bottom” are part of the modern vernacular. It seems like at least one track from every album Drake drops ends up having a “Hotline Bling” type moment where the song becomes so popular it starts getting annoying. Remember the Kiki challenge?

Drake knows how to have fun at his own expense. He cries (and gets absolutely demolished by Marshawn Lynch) in the music video for Life is Good (which takes place at various parts of Nike’s Global Corporate HQ). His album artwork for Views lead to myriad of Photoshops where Drake was perched upon any reasonably elevated location. He made a music video parodying his time on the beloved TV show Degrassi. Drake picks up trash, provides tech support, works in an auto-shop, and flips burgers with Future in the Life is Good video.

This is the same guy who used a lint roller while sitting court-side at an NBA game, the guy who literally gave us a meme template on purpose:

now this is a meme #drake pic.twitter.com/mph8gYbJFv

— FvneMemes✨🌙 (@iamfine111) June 16, 2019

This is too much 😂 I can’t. #Drake #Drizzy #KeanuReeves #YoureBreathtaking #Raptors #Toronto #Canada #Breathtaking #Meme @Drake @Raptors pic.twitter.com/PUXK5YvdMv

— Peter Sark (@petersark) June 18, 2019

Drake clearly understands internet culture — so why is he against AI clones of his music?

If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late

The “Munch” cover was novel, but was definitely not the kind of song I’d listen to more than once.

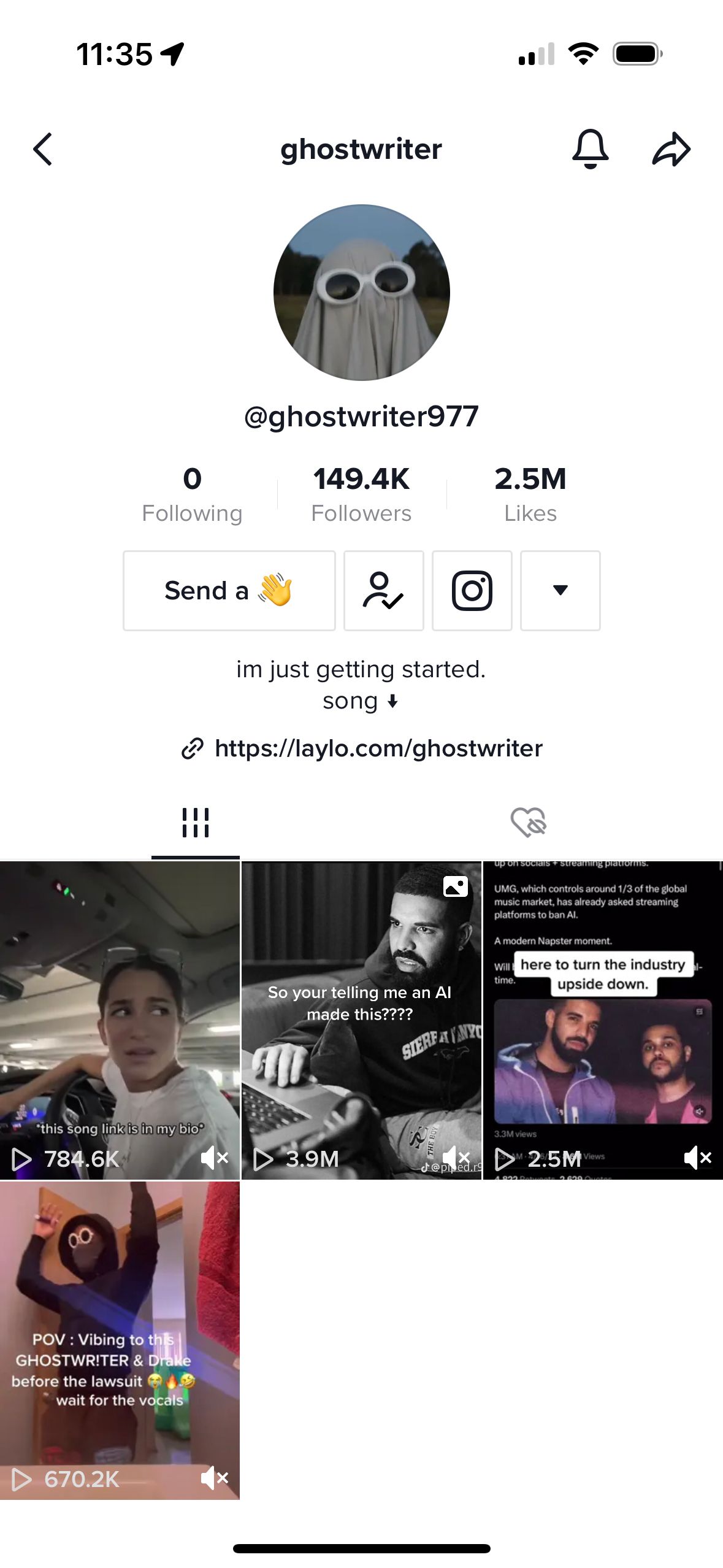

But “Heart on my Sleeve” — a track released by pseudonymous TikTok user @ghostwriter977 — is another story entirely.

If I could, I would listen to this track. But I can’t, because it was scrubbed from YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music, and the rest just days after it was released. From Motherboard:

Ghostwriter used AI to create vocal realistic clips that sound like artists Drake and The Weeknd to create the song, they said on TikTok. The song was introduced on that platform in a video posted over the weekend that quickly gained over 9 million views and inspired thousands of derivative TikToks, and earned hundreds of thousands of plays on Spotify and YouTube by Monday afternoon.

As of Tuesday morning, “Heart on My Sleeve” is no longer available to listen to on Spotify. It does not appear on Ghostwriter’s page and when a user tries to listen to the song through “Ghostwriter Radio”—a Spotify feature—a pop-up advises that the content is not available. At one point, Ghostwriter’s artist page was momentarily inaccessible before quickly coming back online.

Copies of these various AI Drake songs are still floating around the internet, but all of the major links and re-uploads have been flagged for copyright and removed from the internet by Universal Music Group, the record label with which Drake signed a “massive, multi-faceted deal” with in 2021.

This song is a new collaboration between Drake and The Weeknd.

— Trung Phan (@TrungTPhan) April 16, 2023

It’s called “Heart On My Sleeve” and is an absolute banger. It’s also completely AI generated. pic.twitter.com/NLNc6POQYV

AI got Drake rapping “Munch” 😂 pic.twitter.com/pWYB5rcjgg

— Complex Music (@ComplexMusic) April 14, 2023

Legal and content moderation teams alike are working overtime.

When I checked Ghostwriter’s TikTok account, the few videos that were still published also all had the sound muted, a common punishment TikTok doles out to copyrighted content.

When I opened my TikTok app to search for Ghostwriter’s account, the first video I saw was another banger AI Drake song in the same style. It doesn’t seem like these are very difficult to create — I learned myself that making an AI by Balenciaga meme only takes a few hours once you know what you’re doing. More on that in a bit.

@abel_geevarghese ♬ original sound - nvx

Song’s a banger, but I’m not sure how I feel about the “DR-AI-KE” thing.

My former colleagues at The Verge are convinced that there’s some sort of “a scheme” behind the Ghostwriter song:

Ghostwriter’s come-up is strange even for viral TikTok standards. “Heart on My Sleeve” could be a fluky viral hit, a sloppy stunt by a crypto-adjacent startup, a revenge prank by Drake himself, or the beginning of the legal battle over AI-generated work that is flooding the internet. Maybe a combination.

I don’t think it actually matters, at least not unless we find out that it was in fact a conspiracy from some other rapper (or Drake himself) to generate hype. What does matter is that just like the AI by Balenciaga memes, these tracks are getting views.

Views

Drake is so skilled at expressing his ideas that his music videos simultaneously act as an expression of his ideas and serve as a template for his audience to share remixed interpretations of those feelings.

Drake is a master of memes, but for some reason, AI generated music is where Drake draws the line. Why?

Is this just an over-reaction? As Ben Thompson notes, “the record labels, unsurprisingly, learned nothing from the evolution of digital music: their first instinct is to reach for the ban hammer.”

Could it be that Drake simply went to his label and asked them to solve this problem? Did he send an email to his agent that said “I don’t want to be caught singing about that dead, alive, or AI synthesized.”

Then again, of this writing, Drake hasn’t actually commented on the current Ghostwriter situation. The last time he spoke about a ghost writer it was about the noun, not the pseudonymous artist, and what he said is relevant to the conversation.

Thompson provides a solution for proving authenticity in the upcoming era of infinite AI content:

One can make the case that most of the Internet, given the zero marginal cost of distribution, ought already be considered fake; once content creation itself is a zero marginal cost activity almost all of it will be. The solution isn’t to try to eliminate that content, but rather to find ways to verify that which is still authentic. As I noted above I expect Spotify to do just that with regards to music: now the value of the service won’t simply be convenience, but also the knowledge that if a song on Spotify is labeled “Drake” it will in fact be by Drake (or licensed by him!).

This will present a challenge for sites like YouTube that are further towards the user-generated content end of the spectrum: right now you can upload a video that says whatever you want in its title and description; YouTube could screen for trademarked names and block known rip-offs, but that’s going to be hard to scale as celebrities-within-their-ever-smaller-niches proliferate, and it’s going to have a lot of false positives. What seems better is leaning heavily into verified profiles, artist names, etc.: it should be clear at a glance if a video is authentic or not, because only the authentic person or their representatives could have put it there.

If we’re about to enter a world of infinite AI music (which will soon enough evolve to videos and then full-fledged video games), we might as well understand how these AI generated tracks are put together.

There’s also some interesting precedent for AI generated Drake music being removed.

Thank Me Later

Early followers of AI might remember Drayk.it, created by @thisisneer, which had its own viral moment back in late January 2023 when it was picked up by Complex, Pigeons and Planes, and even Hot 97.

Make an AI Drake song about anything 🤖🎵

— neer (@thisisneer) January 24, 2023

1. Type a prompt

2. GPT-3 writes a song in Drake's style

3. AI Drake performs it in < 1 min

Try it here: https://t.co/rzbnVWn9sz pic.twitter.com/yvxUHwKfzr

I had some fun with it before the site was taken down.

AI Drake is afraid of AGI pic.twitter.com/qBapBUYthW

— Gold’s Guide (@goldsguide) January 25, 2023

No individual aspect of the Drayk.it songs are that impressive, but they combine into a package that’s immediately fun and surprisingly simple to use. Too bad it was taken down for copyright. This is the beginning of the trend and serves as interesting precedent for UMG’s actions earlier this week. This is not the first time we’ve heard about serious copyright issues with AI, and it certainly won’t be the last.

How are these AI Drake songs made?

The latest episode of The Vergecast has a fantastic segment where they use the same tools that Ghostwriter used to create their own AI music, featuring Drake, Eminem, and Jay-Z (the full episode is audio only). The songs they make aren’t as good as Ghostwriter’s, but it proves the concept: anyone with a computer can do this.

The tool that makes this happen is called Uberduck. I went to their website and it took me all of two minutes to make this quick rap song using one of their pre-generated voices and provided beats. It’s the same thing as Drayk.it, minus the videos — enter a prompt and it’ll write the lyrics and then sync a voice to them. I didn’t even have to make an account (that said, the song is only a few seconds and includes a subscribe ad at the end).

Proof of concept I created with Uberduck.

Ghostwriter used a more advanced version of the same tool I used to create the above video. While I simply entered an idea for a song and let Uberduck cook, Ghostwriter wrote lyrics that sound like something Drake would actually say (“I got my heart on my sleeve with a knife in my back. What's with that?” is fire) and then rapped those lyrics with a Drake-type flow. All the AI tool had to do was replace Ghostwriter’s voice with one that sounds like Drake.

The tricky thing is creating the Drake-like voice. When I first started playing with ElevenLabs voice synthesis tech, the major caveat with their voice cloning tool was that you can only use voices you have the rights to use (aka yours). Will the internet play by the rules?

What A Time To Be Alive

Following his infamous beef with Meek Mill, Drake spoke in a rare interview with The Fader for their 100th edition (this same passage was quoted in Thompson’s piece):

The fact that most of Drake’s fans seemed not to care about the particulars of how his songs were made proved something important: that Drake was no longer just operating as a popular rapper, but as a pop star, full stop, in a category with Beyoncé, Kanye West, Taylor Swift, and the many boundary-pushing mainstream acts from the past that transcended their genres and reached positions of historic influence in culture. At that altitude, it’s well known that the vast majority of great songs are cooked in groups and workshopped before being brought to life by one singular talent. That is the altitude where Drake lives now.

“I need, sometimes, individuals to spark an idea so that I can take off running,” he says. “I don’t mind that. And those recordings—they are what they are. And you can use your own judgment on what they mean to you.” “There’s not necessarily a context to them,” he adds, when I ask him to provide some. “And I don’t know if I’m really here to even clarify it for you.” Instead, he tells me he is ready and willing to be the flashpoint for a debate about originality in hip-hop. “If I have to be the vessel for this conversation to be brought up—you know, God forbid we start talking about writing and references and who takes what from where—I’m OK with it being me,” he says.

He then makes a bigger point—one that sums up why the experience of being publicly targeted left him in a position of greater strength than he went into it with: “It’s just, music at times can be a collaborative process, you know? Who came up with this, who came up with that—for me, it’s like, I know that it takes me to execute every single thing that I’ve done up until this point. And I’m not ashamed.”

It’s not hyperbole to say that Drake is one of the most powerful musicians in the history of music. He has the best access in the world; beats, lyrics, ideas, trends, it doesn’t matter.

If Drake — who’s at the top of his game and not going anywhere — has ghostwriters to help perfect every word of his lyrics and has a team of engineers obsessing over every detail of every beat, perhaps up-and-coming artists can leverage AI to get access to similar levels of support at a fraction of the cost.

Imagine an AI model that’s been fine-tuned on the best rap songs of all time. Individual artists could create their own writer’s rooms to bounce ideas back and forth with an AI with a knowledge of the greatest songwriters in history. The model could theoretically be tuned to omit certain musicians the artist using it doesn’t like, or could be weighted to take more influence from some musicians than others.

Fully AI generated music is a long ways away, but in that world, it feels like everyone will get “promoted” to a position where editing and guiding an AI model will provide results that resemble the output of a full team of ghostwriters, or even a Rick Rubin type position where a human tastemaker “produces” music from various AI models.

Rick Rubin became a world-class music producer without knowing the first thing about music pic.twitter.com/3DhJi0IpK0

— David Perell (@david_perell) January 16, 2023

If the copyright claims continue, it’s also possible that we see a resurgence of mixtape culture — secret AI songs that are serious and humorous using illegal voice clones of famous artists. Back in the 90’s, recording a song from the radio to a tape cassette was illegal-but-normal, just like it was illegal-but-normal to download a track from Napster in the early 2000’s and burn the tracks to a CD to play in the car or share with a friend.

Maybe these copyright issues are a temporary issue, or maybe they’re going to be the blocker that prevents AI music from taking the next step. What’s clear is that the artists who can leverage this tech to create novel and compelling music will be the ones to succeed.

Update, literally ten minutes after publishing: right after I sent this out as an email, I went on Twitter and saw this tweet from Grimes:

I'll split 50% royalties on any successful AI generated song that uses my voice. Same deal as I would with any artist i collab with. Feel free to use my voice without penalty. I have no label and no legal bindings. pic.twitter.com/KIY60B5uqt

— 𝔊𝔯𝔦𝔪𝔢𝔰 (@Grimezsz) April 24, 2023

There are so many more of these music generation apps I might do a full review of the space, but for now I hope I’ve provided a good starting point. I’m looking forward to seeing what other artists think of this. Grimes is a fitting early adopter; we’ll see how the rest of the industry responds.