The deep history of CNET spans back to the early 1990’s, when the “Computer Network” launched as a 24-hour television network covering computers and electronics.

In its early days, the company produced TV shows that aired on the USA Network and the Sci-Fi channel — I bet you had no idea that years before you saw him on American Idol, a young Ryan Seacrest hosted one of CNET’s first tech shows in the early 90’s.

via YouTube

The Golden Era of Gadgets

By the time the original iPhone ignited a Cambrian explosion of technology journalism in 2007, the bright red CNET insignia was the most recognizable brand in the burgeoning space. Their venerability was emphasized at the peak of post-iPhone tech media hype in 2008 when CBS purchased CNET for $1.8 billion.

CNET set the original standard for modern gadget reviews, especially with video — check out these classics on the first iPhone and the original Motorola Razr and Droid. My personal favorite series on CNET was Prizefight, which pitted devices against each other by comparing their strengths and weaknesses.

Early CNET editors like Veronica Belmont, Brian Tong, Molly Wood, and Bonnie Cha had established themselves as recognizable and trusted faces years before social media creators would take on similar roles.

During this era, CNET also hosted the original Download.com, a kind of App Store before the App Store where I remember downloading all kinds of applications for the slate-gray Dell desktop which I monopolized from my family in my youth. The Download.com garden was not as neatly pruned as the modern day App Store and I have some sharp memories of narrowly avoiding (and painstakingly uninstalling) spam and viruses.

CNET would encounter its first rivals in digital-native upstarts like Engadget and Gizmodo and TechCrunch. Theirs is a classical story of disruptive innovation: these new digital first properties (we can call them “blogs” if we really have to) were more agile and prolific than CNET — but at first, had significantly lower production standards.

When The Verge launched in 2011, it presented the first true existential threat to CNET.

Full disclosure: I worked at The Verge from its launch up until 2014, and remember when we had upgraded from a single trailer to a double-wide trailer about the same size as CNET’s at CES 2013.

That same year, CNET became the most talked-about technology publication at CES... for all the wrong reasons.

Scandal in Sin City

Before the internet, conferences like CES and MWC were the best way for manufacturers to share their products and stories with the press.

Epoch-defining products like the first VCR boxes, the Atari Pong console, the first CD players, and the original Nintendo Entertainment System were all announced at CES conferences. Apple even announced the Newton there.

CES is still around today, but it’s far less significant in a post-internet world.

CNET was the subject of perhaps the least interesting scandal that ever took place in Las Vegas.

In 2013, CNET was by far the biggest media presence at the largest annual tech conference. I remember The Verge team feeling like David compared to their Goliath. Just look at the full production studio they had, located right next to the entrance of the convention center. While the rest of the tech press was forced to record their videos out on the chaotic show-room floor, CNET had a private lounge.

In retrospect, 2013 would end up being peak CNET. From The Verge:

On Friday, news broke that CNET had been forced by its parent company CBS to remove the Dish Network's Hopper set-top box from its "Best of CES" awards due to ongoing litigation between the two companies. CBS has been battling the Dish Network in court over the Hopper's ability to skip past commercials automatically (NBC, ABC, and Fox are also taking action).

Since we’re talking about DVRs, I’ll keep this part as brief as possible.

- CNET awarded the Dish Network Hopper (a DVR set-top box that could automatically skip TV commercials) the title of best product of CES 2013.

- But CBS — CNET’s parent company at the time — was actively battling Dish in court over the same exact commercial skipping technology that was the reason CNET awarded this product the top position.

- CBS forced CNET leadership to change their decision and disqualify the Hopper, raising fundamental doubts about CNET’s editorial independence. If CBS overruled CNET’s editors once, what’s preventing it from happening again?

This was a huge debacle that suddenly threw CNET’s entire reputation into question — unleashing a tidal wave of corrections, retractions, and bad publicity.

By the time the iPhone X was released in 2017, The Verge was the heir apparent to the tech media throne, MKBHD’s audience numbers were hockey sticking, and legions of YouTubers were clamoring for a piece of the action. CNET was feeling increasingly boring, especially after Brian Tong left CNET in 2018 to start his own YouTube channel.

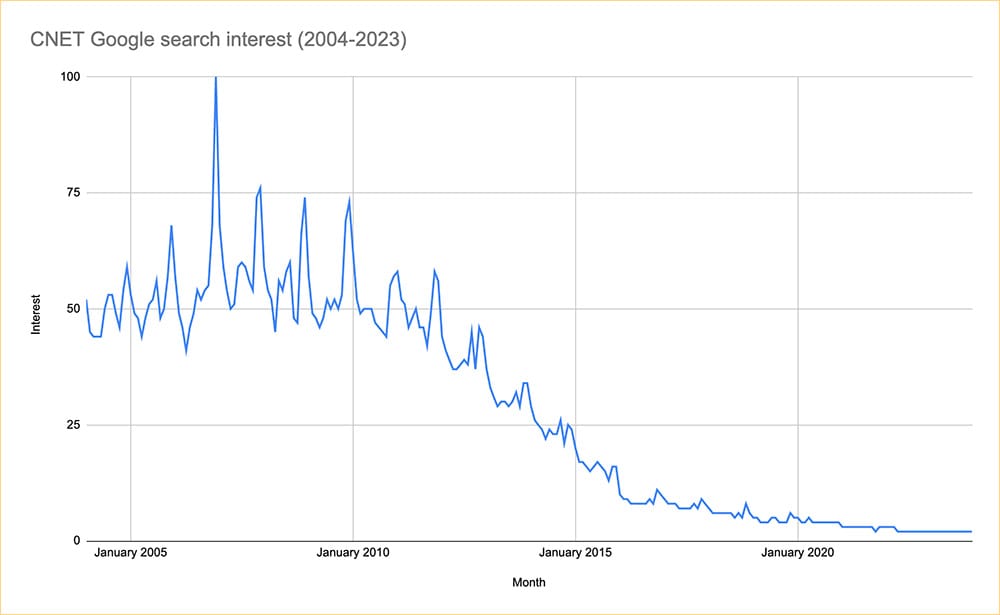

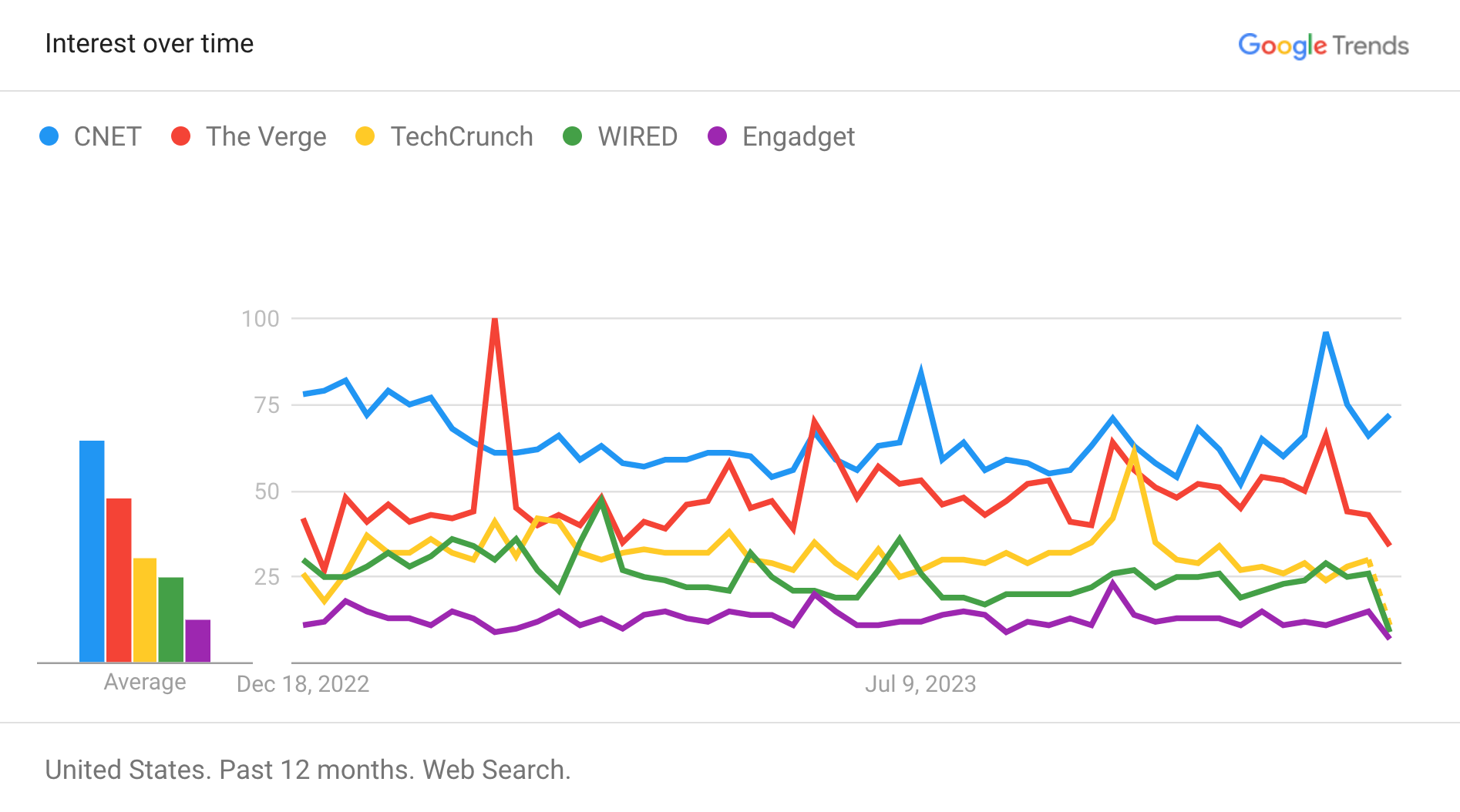

Google Trends correlates with my experience:

As the underdogs ascended, CNET fell off my radar until 2020, when they celebrated their website’s 25th birthday. A few months later, news broke that CNET was being sold by CBS.

The lucky new owner? Red Ventures, who picked up CNET for just $500 million — a paltry 28% of the $1.8 billion that CBS purchased the company for in 2008.

Quarter-life Crisis

Shortly after the RV acquisition in 2022, CNET introduced a major rebrand, trading their classic red circle logo for a more minimal and “streamlined” look.

Left: the original CNET logo. Right: the current CNET logo. Personally, I dislike the “N” — it looks like a rotated “Z”. (via Logopedia)

Here’s CNET’s EVP of Content and Audience Lindsey Turrentine (who has worked at the company in various roles since 1999) on the new identity:

Our new brand mark gives a nod to the era of the letterpress, but with a modern turn in recognition that the best information and advice is simultaneously timeless and unafraid of the future.

The original CNET logo was iconic — to fundamentally change it in such a drastic way was a clear indication of a new mission, which was hinted at in Turrentine’s letter.

Nothing in this world is simple. How do you decide if you should invest in crypto, what's best to stream tonight or whether weight training might help you live longer? What should you consider when you want to buy a TV, if maybe projectors are the future? Should you think about a mortgage in the West now that every year has a fire season?

As far as I know, CNET historically didn’t talk much about mortgages... but Red Ventures media properties sure do. The relatively obscure holding company operates a sweeping portfolio of high-traffic media brands including The Points Guy and CreditCards.com.

I had never heard of Red Ventures until I read Ben Smith’s 2021 column in The New York Times, which was appropriately headlined “You’ve Never Heard of the Biggest Digital Media Company in America”:

Red Ventures, which started as a digital marketing company, has attracted serious investments from private equity firms. Its location has helped obscure what is perhaps the biggest digital publisher in America, a 4,500-employee juggernaut that says it has roughly $2 billion in annual revenues, a conservative valuation earlier this year of more than $11 billion, and more readers, as measured by Comscore, than any media brand you’ve ever heard of — an average of 751 million visits a month.

Indeed, despite the huge decline in Google search interest for CNET we saw earlier, CNET is still the most popularly searched name in tech media:

All of the RV brands seem to follow a similar playbook: monetize strong search engine optimization with hefty bounties for referring a customer to a purchase (and plenty of advertising). Again, Smith:

In 2015, Red Ventures raised $250 million, which went toward its $1.4 billion purchase of Bankrate, a personal finance company that helps people comparison shop for financial products (and earns a commission on each sale). That acquisition included The Points Guy, a site devoted to elucidating airline mileage programs and credit card deals. The Points Guy had built a profitable business earning commissions whenever people signed up for credit cards they had read about on the site — often in rave reviews of high-end cards.

The marketing of financial products promises far higher profit margins than the online “affiliate” businesses that underlie websites like The New York Times’s Wirecutter. While a publisher recommending a gadget on Amazon might earn a single-digit percentage of a shopper’s purchase, the “bounties” paid to Red Ventures for directing a consumer to a Chase Visa Sapphire Reserve credit card or an American Express Rose Gold card can range from $300 to $900 per card.

Here’s an analogy: if traditional media advertising is like farming, then the Red Ventures link bounty business model is like fishing.

- Farming requires long-term planning, patience, and scale, but in a healthy environment, it will deliver reasonably predictable results.

- Fishing delivers less predictable but instant results... of varying sizes. Sometimes you might catch nothing, sometimes you might catch a huge trophy fish.

It appears to me that Red Ventures is attempting to build what amounts to a digital fishing factory, where they found a certain type of fish (aka credit card bounties) and are now attempting to catch as many of them possible. Not to beat this metaphor to death, but the problem is that RV seems to be succumbing to is the very same problem that the plagues the fast food industry: prioritizing efficiency and profit before quality.

Artificial Information

In 2023, CNET became one of the first mainstream publications to utilize generative AI.

It sounds cool in theory, but the problem with articles generated by artificial intelligence is that it’s totally undifferentiated... I can just ask an AI myself.

Maybe it would be interesting if the AI provided bespoke content designed just for me, but this method feels lazy and devalues all the content that the humans employed by CNET work hard to produce. This sort of AI content appears to be a clear attempt to extract every drop of possible remaining value.

Perhaps that’s why when CNET introduced these artificially generated stories, there was no fanfare, no announcement post, and no updated editorial policy. The introduction was so low-key that it inspired suspicion, which as reported by Futurism, was for good reason:

Take this section in the article, which is a basic explainer about compound interest (emphasis ours):

"To calculate compound interest, use the following formula:

Initial balance (1+ interest rate / number of compounding periods) ^ number of compoundings per period x number of periods

For example, if you deposit $10,000 into a savings account that earns 3% interest compounding annually, you'll earn $10,300 at the end of the first year."

It sounds authoritative, but it's wrong. In reality, of course, the person the AI is describing would earn only $300 over the first year. It's true that the total value of their principal plus their interest would total $10,300, but that's very different from earnings — the principal is money that the investor had already accumulated prior to putting it in an interest-bearing account.

"It is simply not correct, or common practice, to say that you have 'earned' both the principal sum and the interest," Michael Dowling, an associate dean and professor of finance at Dublin College University Business School, told us of the AI-generated article.

Regardless of if the content was generated by an AI or created by a human, this is exactly the kind of blatant mistake an editor is supposed to catch!

That’s not even the worst part. From that same Futurism article:

It's a dumb error, and one that many financially literate people would have the common sense not to take at face value. But then again, the article is written at a level so basic that it would only really be of interest to those with extremely low information about personal finance in the first place, so it seems to run the risk of providing wildly unrealistic expectations — claiming you could earn $10,300 in a year on a $10,000 investment — to the exact readers who don't know enough to be skeptical.

I don’t think we have anything to celebrate or tell.”

— Red Ventures CEO Ric Elias, 2021

The Ship of Theseus

In summer 2021, just a few weeks before the NYT published their piece declaring RV the biggest digital media company in America, the economy was on the rise, and CNET announced they were hiring for 150 new roles.

When it works, the bounty business model works to extraordinary effect — but perhaps it’s just as correlated to the fluctuations of the broader economy as advertising, because barely two years later, the outlook was not as rosy. CNET underwent layoffs in March 2023.

CNET’s audience is still incredibly large, apparently reaching over 65 million monthly visitors — but I don’t know who those people are anymore. If CNET sees as much traffic as Red Ventures says they do, I’d imagine that CNET’s average reader is significantly older than the average demo of any of its competitors.

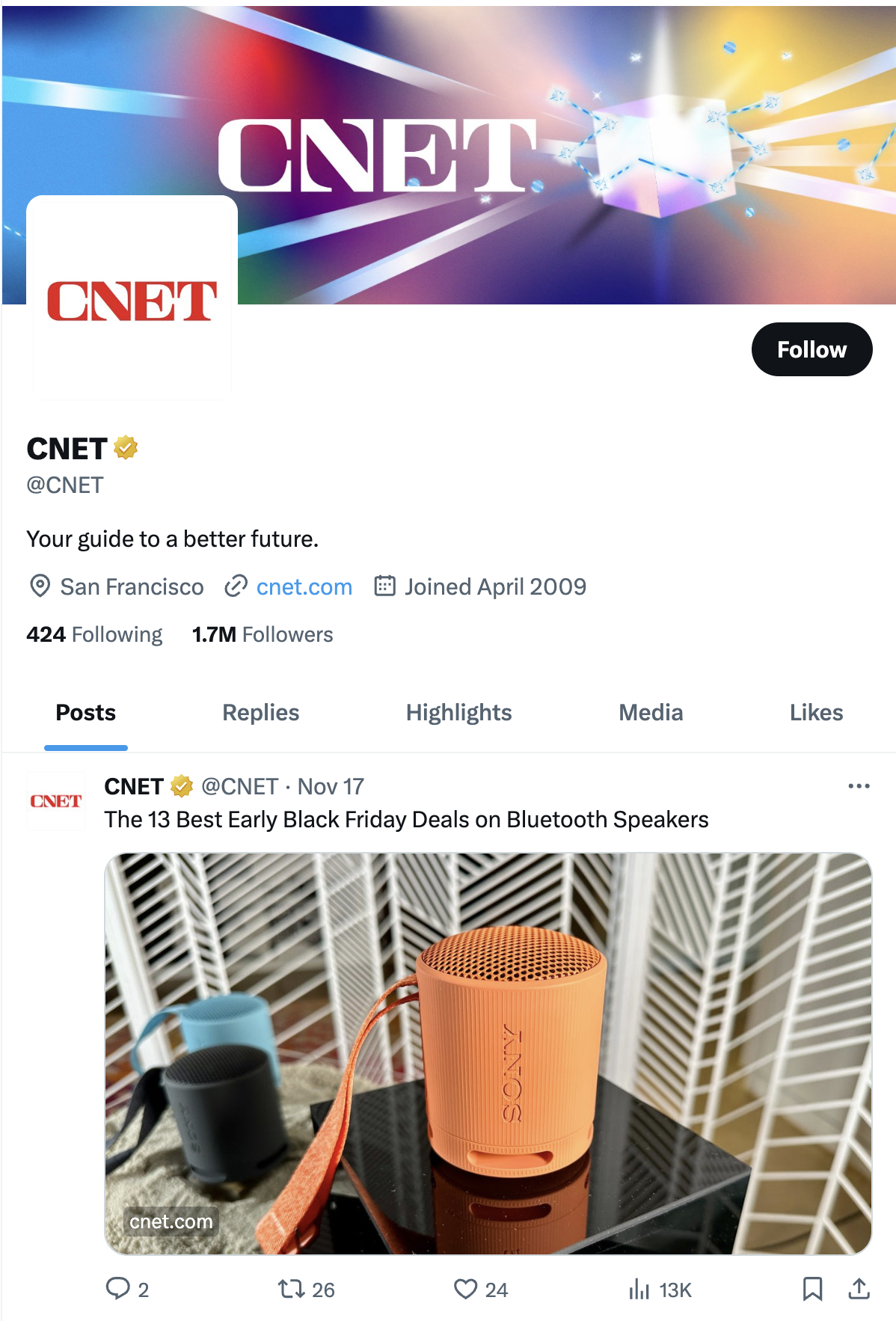

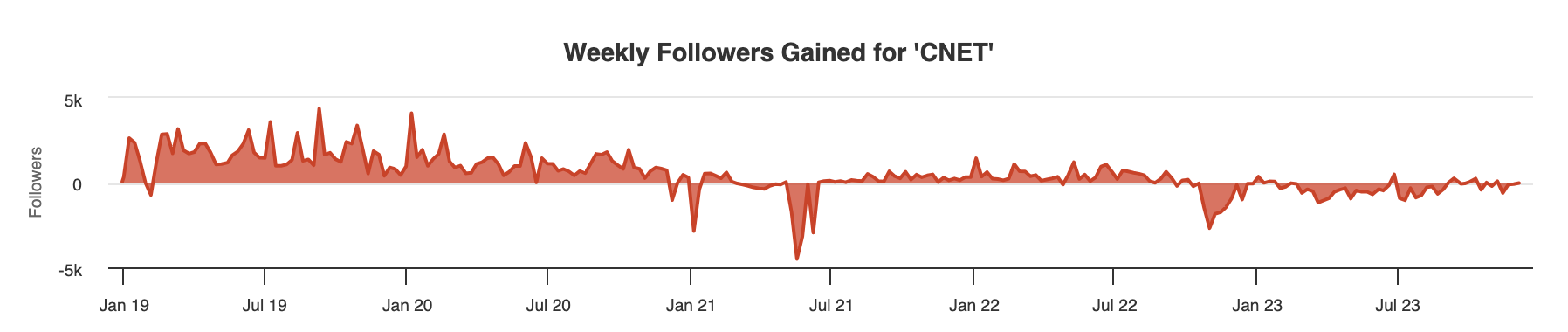

They certainly aren’t using 𝕏: the @CNET account isn’t just losing followers (-27,761 since Nov 2022, according to SocialBlade), but despite apparently paying for gold check verification, they didn’t post anything on 𝕏 for over a month.

Between November 17 and December 20, 2023 there were zero new posts on the CNET 𝕏 account — and when they did start to post again, the content almost entirely appears to simply be automated posts with a link and headline.

This shifting social output is probably a sign that their audience is more of a one-time visitor than loyal followers. Social media platforms are almost certainly less impactful to CNET’s bottom line than search results, and I think most of their traffic is coming from people interested in a review of some random laptop at Costco, not the latest flagship from Lenovo or Apple.

The fact that so many of the Red Ventures portfolio sites monetize within such a specific area of credit card affiliate commissions (The Points Guy and CreditCard.com target the same market) makes it seem like RV is attempting to corner what they perceive as a lucrative corner of the market. And it probably is lucrative!

The problem is, at the end of the day, this apparent pursuit of profit above purpose has rebranded not just an iconic logo, but the entire essence of the internet’s most storied technology reviews website. I understand that Red Ventures is running a business, but at what point does chasing profit outweigh providing a quality product? It’s a delicate balance.

I wonder if under Red Ventures ownership, CNET is a solution to the Ship of Theseus paradox — because even though it’s still the same website, over the years CNET has had so many critical parts altered or replaced that it’s clearly no longer the same website.

Image Sources

- Lead image sources, starting from the top and going down per row from the left to right:

- Halsey Minor headshot (TechCrunch)

- Shelby Bonnie headshot (The Hotchkiss School)

- Staff photo (CNET.com, 2020)