Last year, after more than a decade of getting my information from social media, I switched back the original newsfeed: RSS.

Unlike our Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok feeds — impermeable black boxes which are completely controlled by their respective companies — RSS is like email in that it isn't "owned" by any individual company or entity. It's an open format, which means that anyone can create their own RSS feeds, apps, or services.

With RSS, what's old is what's next.

Social media isn't good anymore

Each day on twitter there is one main character. The goal is to never be it

— maple cocaine (@maplecocaine) January 3, 2019

In a poetic twist, the very spur-of-the-moment spontaneity that made Twitter (and Facebook, Instagram, etc.) interesting, even magical, in the first place have made those places... bad.

It's no surprise that people are becoming less-and-less comfortable with sharing on public social stages and increasingly prefer to spend more-and-more time in private spaces like direct messages, group-chats, and email newsletters.

In his Dark Forest Theory of the Internet, Kickstarter cofounder Yancey Strickler describes the public internet of the late 2010's and early 2020's as a social battleground of hostile ideas and viral information, a transformation which has shifted discourse towards more private spaces:

In response to the ads, the tracking, the trolling, the hype, and other predatory behaviors, we’re retreating to our dark forests of the internet, and away from the mainstream.

The concept of the mainstream is both new and powerful. The mainstream is only for the most significant moments — big life-updates, amazing moments, epic vacations. Personally, I haven't regularly posted to my personal Instagram page since 2018, but I have DM group-chats I check almost every day. Similarly, the ephemerality of stories (which Insta and Twitter shamelessly copied from Snapchat) has filled some of the void for daily sharing — but it's clear that we are still in the early days of understanding the impact of the social networks. Strickler writes:

Dark forests like newsletters and podcasts are growing areas of activity. As are other dark forests, like Slack channels, private Instagrams, invite-only message boards, text groups, Snapchat, WeChat, and on and on.

The industry is aware of this, of course: Facebook has television commercials promoting FB Groups encouraging communities based around identities. Twitter is pushing out its new Spaces product to compete with Clubhouse. Just this week, Discord allegedly turned-down a $12 billion dollar offer from Microsoft.

The once-innovative social networks have become lumbering behemoths; uninspiring, untrustworthy, and boring. It was 2014 when Facebook officially changed their motto from "move fast and break things" to "move fast with stable infrastructure." The disruptors have become the incumbents, and the new dynamic is all still being figured out.

Social media is in a pre-Newtonian moment, where we all understand that it works, but not how it works.

— Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom to Kara Swisher after he quit Facebook in 2018

Exploring the forest

There's more innovation happening on the internet than ever before — it just seems to be happening away from the hugely public mainstream and in more personal spaces.

New creative economies are just beginning to boom: the next wave of creators, artists, and entrepreneurs are already producing, sharing, and monetizing their personal passion, unique experiences, and specific knowledge by going directly to their audiences, fans, and customers.

Personalities like Li Jin, Taylor Lorenz, Joseph Albanese, and Colin and Samir have already begun to carve out their own sort of meta-niches covering the creator economy itself. More and more people are beginning to recognize the power of owning a creative business.

The email renaissance

I think this is a huge part of the reason email has become so popular recently.

Compared to the highlight-reel of the mainstream, the "non-indexed, non-optimized, and non-gamified" culture of email newsletters is a breath of fresh air. There's also the sense of direct connection: when a reader signs up for a newsletter, they are clearly saying they want to get that email. Even further, says Craig Mod, a writer who has something like six email newsletters, email allows creators and writers to actually own the connections they have with their audiences instead of leasing them out to Facebook or Twitter:

Ownership is the critical point here. Ownership in email in the same way we own a paperback: We recognize that we (largely) control the email subscriber lists, they are portable, they are not governed by unknowable algorithmic timelines.

And this isn’t ownership yoked to a company or piece of software operating on quarterly horizon, or even multi-year horizon, but rather to a half-century horizon. Email is a (the only?) networked publishing technology with both widespread, near universal adoption, and history. It is, as they say, proven.

There's just one catch with this second-coming of the email newsletter: email is a tool I associate with work, not a pleasant reading experience.

Maybe this is a personal problem, but... I don't like email.

That's where RSS comes in.

The all natural newsfeed

RSS has no processed information spam, no artificial algorithms, and no troll comments — and the most recent posts are always at the top.

RSS is a distraction-free newsfeed. Instead of checking social media or email, I check an app that's dedicated to one purpose: reading.

I've been using RSS as my main newsfeed for the last year now. It's a focused place for me to organically learn about the things I want to learn.

I think that RSS — despite being old tech — is what's next for information consumption.

Information from people, not machines

RSS lets you subscribe to the websites or newsletters that you want to get updates from, and then it only shows you new posts from those sources.

There's no retweets, no sharing, no random trending events to distract your attention: just pure, quality information. The only surprises are the kind I want to see — a collaboration between two of my favorite thinkers, a deep-dive article into a topic I'm interested in, a new product or software update.

Instead of these serendipitous moments happening based off my inputs into an algorithm, cultivating a good RSS feed has allowed me to stay on top of the information I care about while also creating an environment where ideas, not outrage, are what gets magnified.

A brief history of RSS, the original aggregator

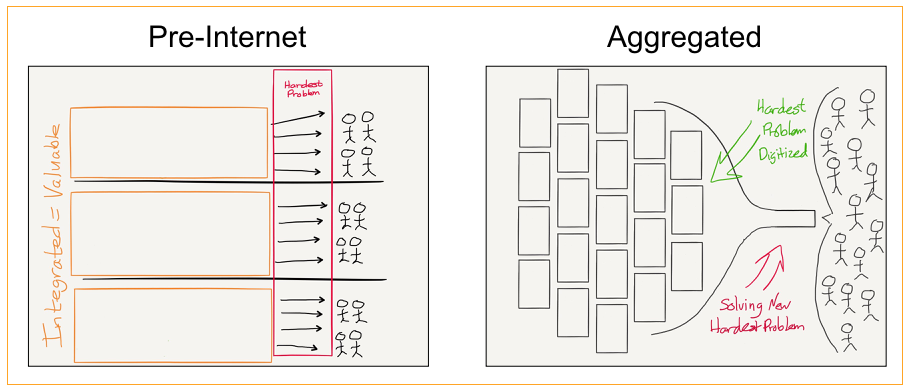

Even back in the early 2000's, there was way more information on the internet than any one person could consume. RSS was one of the earliest solutions; an aggregated feed collecting content into one, centralized place for reading all of the internet's news, blogs, websites, and magazines you were interested in.

RSS perhaps reached its zenith of popularity when the New York Times adopted it for their site in 2005. Walt Mossberg marked the moment in the WSJ with a Guide to Using RSS, Which Helps You Scan a Vast Array of Websites:

If you read a dozen or more online news sites every day, managing them all can be difficult. In the most popular Web browser, Microsoft's Internet Explorer, you have to laboriously open them one at a time. You can open each in a separate window, but the windows pile up in the task bar at the bottom of the screen, making a visual mess that is hard to navigate. [...]

So power users have been employing a system called RSS that allows them to quickly scan large numbers of newsy, frequently updated Web sites. RSS, which stands for Really Simple Syndication, is a kind of computer code that Web site owners can add to their sites to make them easier to scan quickly.

When interpreted by special RSS-savvy software programs called "news readers" or "news aggregators," the RSS code allows these programs to display only the headlines and short summaries of these news sites' latest articles. This is called an "RSS feed." Users can "subscribe" to various feeds and quickly scan the headlines and summaries. Then, if they so choose, they can click on a link to read the entire article.

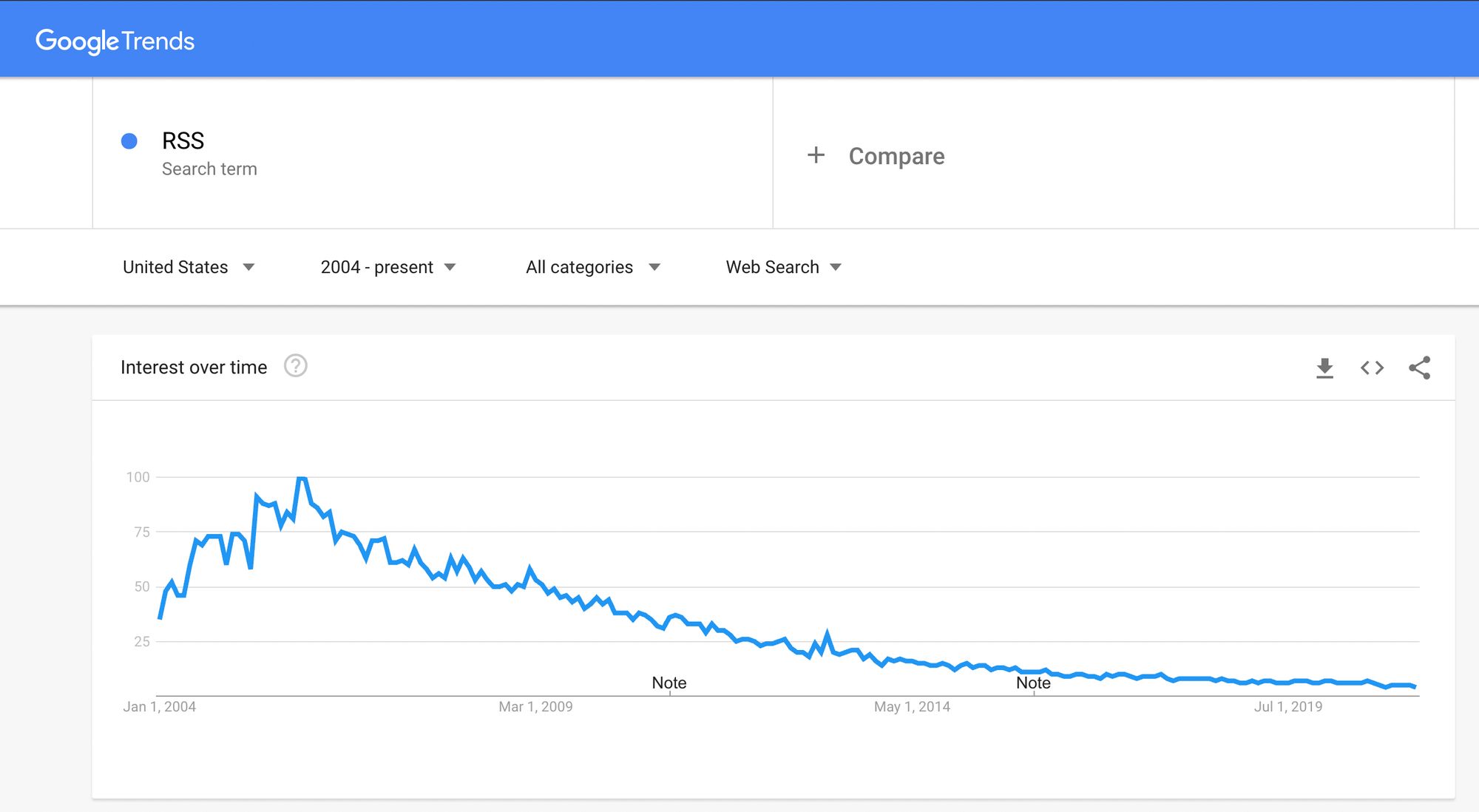

Then Facebook introduced the News Feed in 2006, Twitter exploded in popularity in March 2007 at SXSW, and interest in RSS has seemingly been on the decline ever since.

Many saw the 2013 shutdown of Google Reader, a darling of the original era of syndicated feeds, as the final domino to fall in the gradual demise of RSS.

But despite the cult-community of RSS users, it never really reached anything close to becoming the mainstream that Facebook, Insta, or Twitter have become for so many.

Who is going to tell the normal people that RSS is dead?

— M.G. Siegler (@mgsiegler) March 14, 2013

Wait.

Who is going to explain to normal people what RSS was?

Back in 2013, the idea of a newsfeed itself was still relatively novel — let alone the idea that social media would replace television as the mainstream. But in 2021, feeds have become our default means for acquiring information. RSS is an open alternative to the big social media feeds we've become accustomed to.

Because it's an open standard, RSS is still everywhere

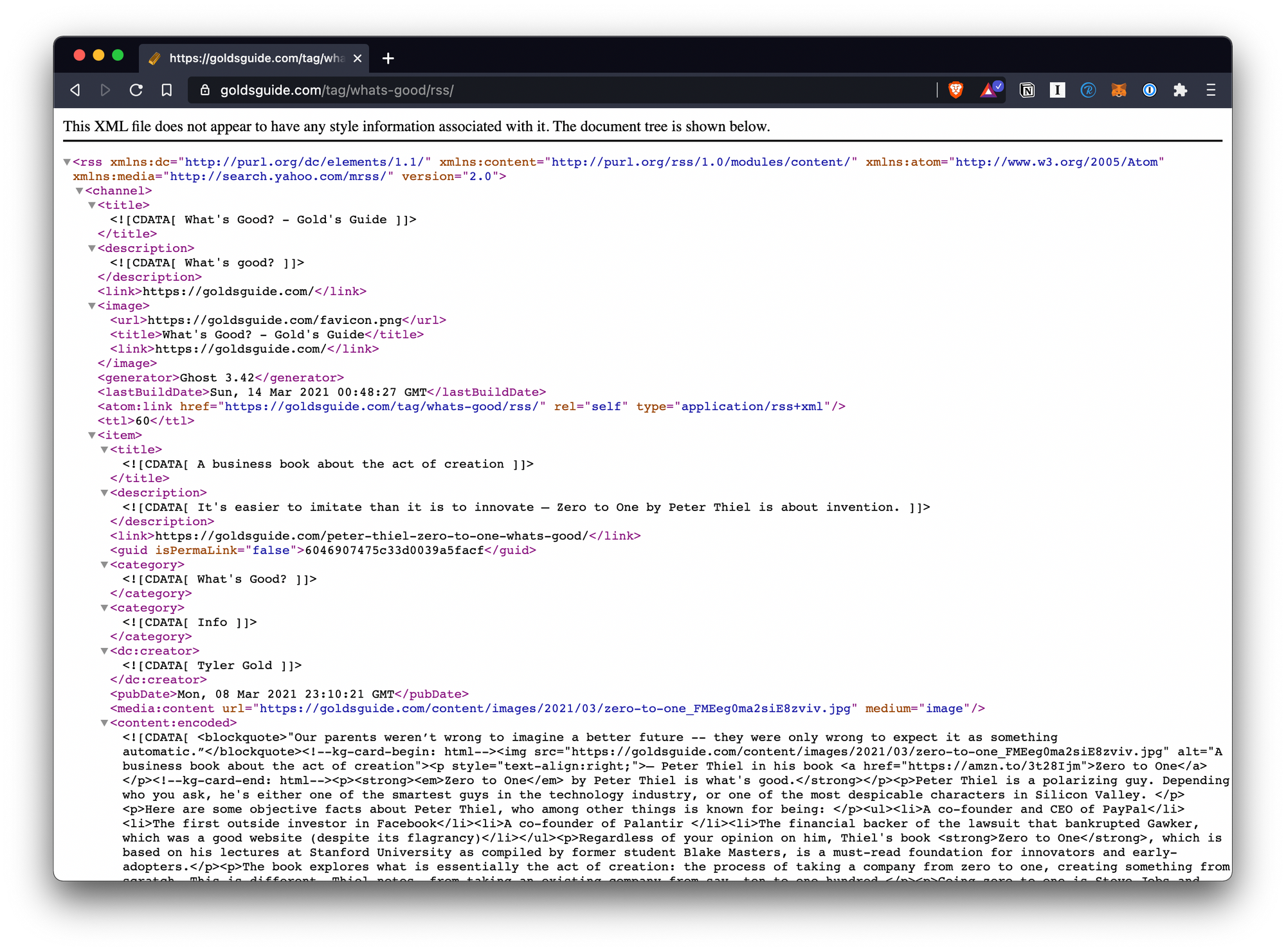

Since RSS is an open format, like HTML or email, it can be used by anyone.

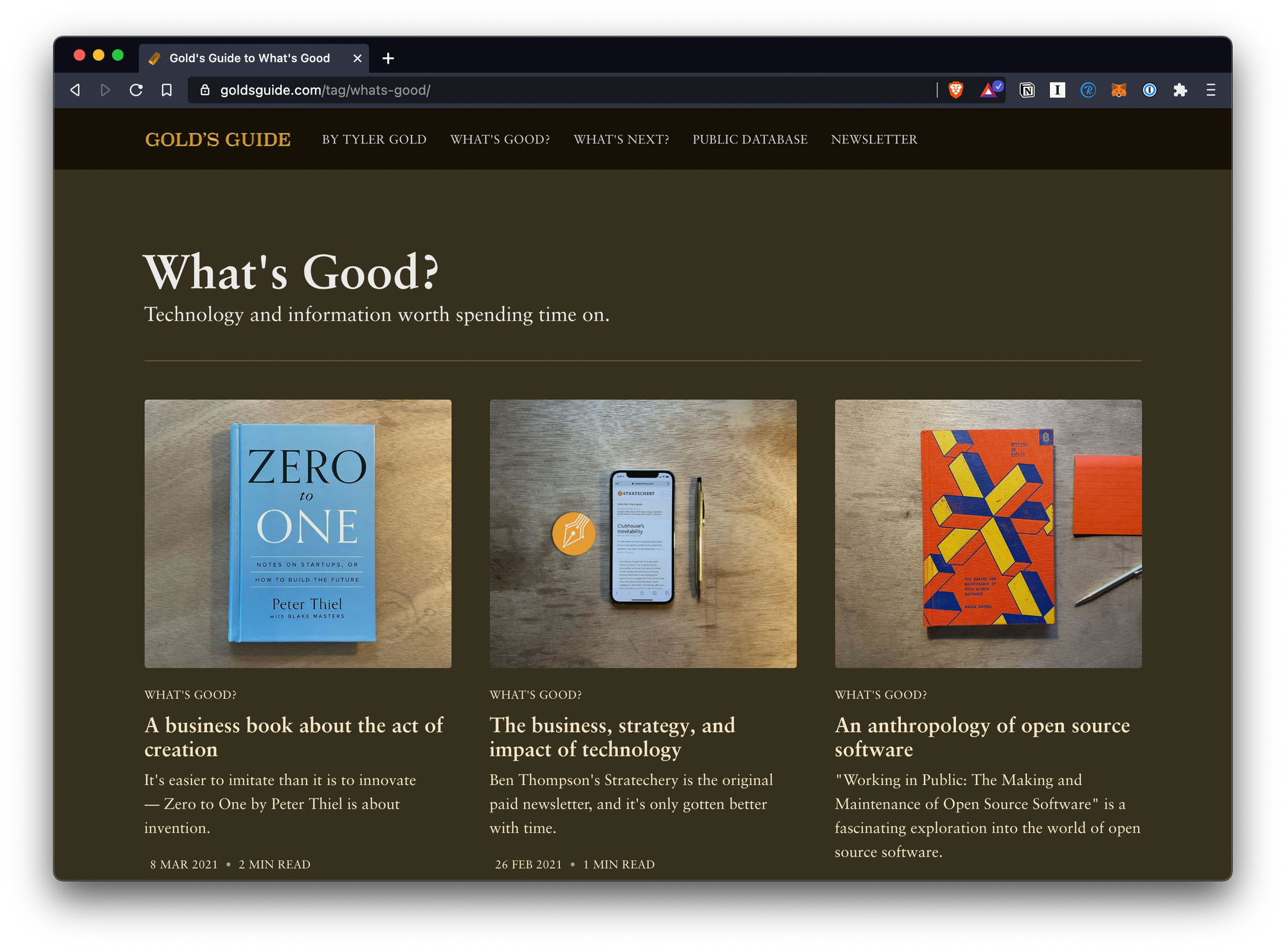

Pretty much every website still has an RSS feed, from one-person blogs like Daring Fireball and Kottke.org and Gold's Guide, to huge publications like the New York Times.

Left: the page on the Gold's Guide website for What's Good. Center: the RSS feed for What's Good. Right: the What's Good feed viewed in NetNewsWire RSS reader (they all display the same content)

If that weren't enough: RSS is also the underlying technology that powers podcasting.

RSS is also the foundation of podcasting

When you subscribe to a podcast in any app that's not Spotify, you're subscribing to an RSS feed for that podcast. Your podcast app (Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Castro, etc) interprets the feed, pulls out the artwork and audio file, and then shows a list of episodes for the podcast shows you follow or subscribe to and lets you listen to them.

Spotify has become an increasingly dominant player in podcasting of late; they offer a centralized version of podcasting that is akin to the dynamic Facebook / Twitter have with RSS feeds. More on that in a future article; we're here to talk about reading apps.

Bring your own app

Back in the day, Google Reader was the most popular way to read RSS because it was more than just a reading app; it also synchronized all your sources across devices.

We take for granted that our Twitter feeds are the same on our phones and on our computers; just like the social aspects of the mainstreams, the open format of RSS cuts both ways. RSS doesn't have a built-in sync feature. When Google Reader shut down, it became increasingly difficult to sync your RSS feeds since most of the reading apps at the time didn't have their own sync services.

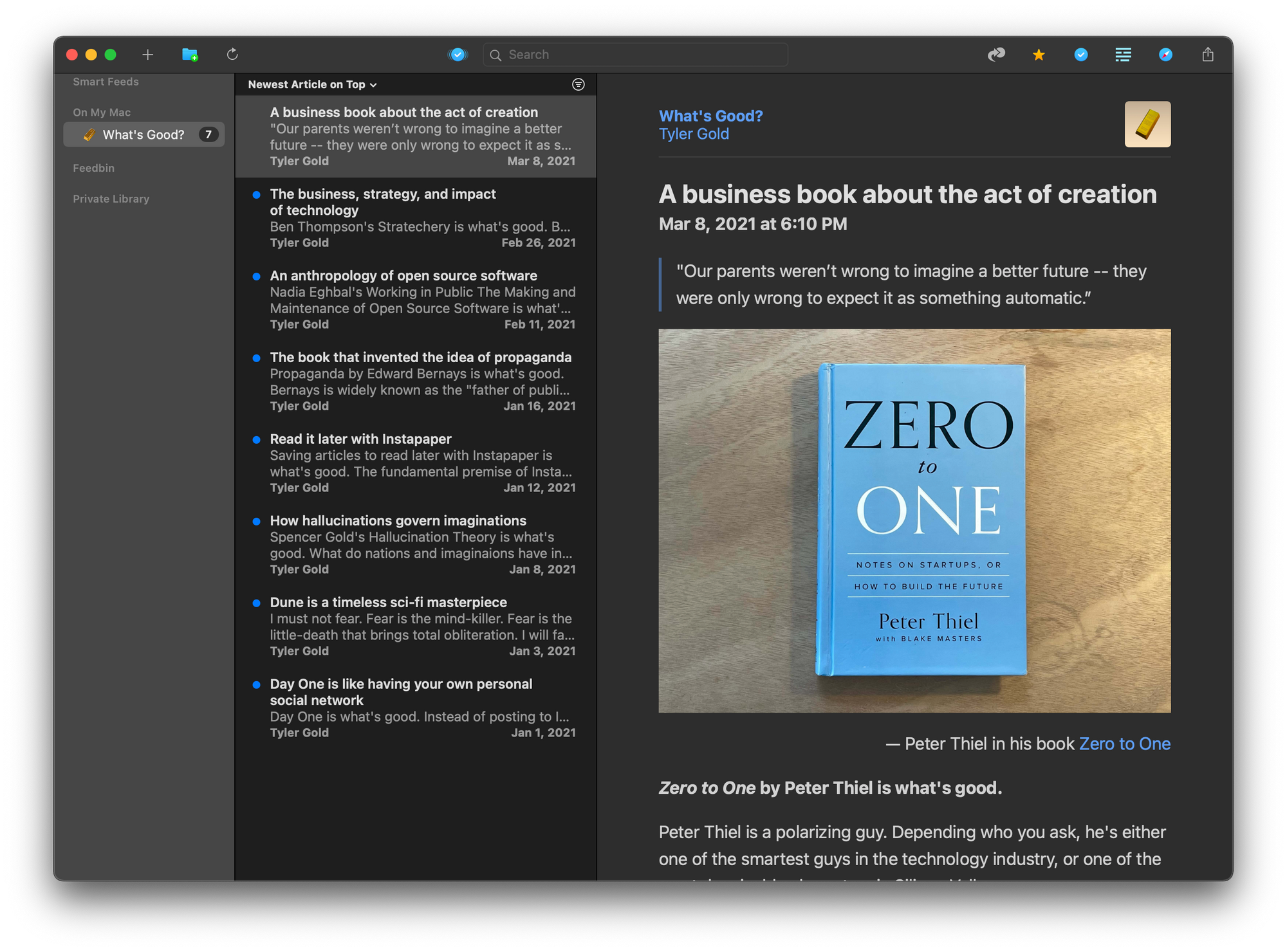

RSS reading apps are a playground for interesting user interface and software design. Because the RSS tech itself hasn't changed much over the years, the reading apps used to access them can work on new features. There are tons of great reading apps for every platform, including iOS, Android, Mac, Windows, and of course, the web.

RSS never died, it evolved.

Paying for the product

The mainstreams feel more like vehicles for advertising than for content; Instagram shows me an ad every four posts, and I get an ad on Twitter every six tweets.

Instead, I use a service called Feedbin to sync my RSS reading list across my phone, laptop, and tablet, and to collect email newsletters in a dedicated app just for reading. It costs $50 a year (or $5 per month) and it's so worth it. From my article about why Feedbin is what's good:

Instead of entering your personal email address when signing up for the latest Substack or the best morning newsletter, you can just enter a secret email address provided by Feedbin, and fresh newsletters will be automatically delivered to your dedicated RSS app for distraction-free reading outside of your email inbox. It's amazing.

Feedbin provides such an incredible reading experience that for me, it's a no brainer. To be able to keep up with my favorite sources of information in a quiet environment without ads or trending pages is well worth it.

Then, I sync my Feedbin account in to NetNewsWire or Reeder.

The end result

Further reading

Motherboard published this epic deep-dive into the history of RSS, including the circumstances of its initial creation back in January 2019.

Ryan Broderick (formerly of BuzzFeed and the internet-at-large) wrote a great take on what it means to be the "main character of Twitter" — his insight into the exact Moment That Twitter Became a Dying Website (December 20, 2013) is spot-on.